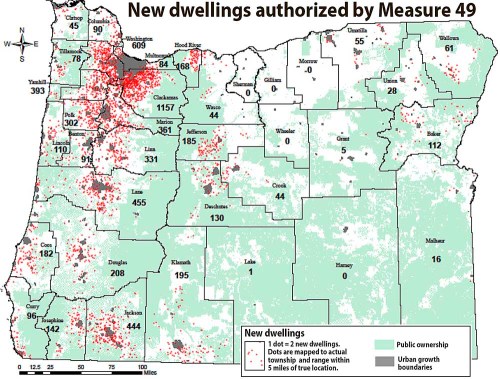

Most Oregon Measure 49 properties remain undeveloped

Published 6:00 am Friday, November 29, 2019

- Oregon Dept. of Land Conservation and Development

SALEM — Most of the farm and forest properties made available for development in Oregon under a decade-old ballot initiative haven’t yet been subdivided, according to state land use regulators.

Meanwhile, county governments and affected landowners don’t appear eager to take advantage of a program that would steer home-building away from more valuable natural resource lands.

Of the properties that have been subdivided under Measure 49, a property right law passed in 2007, about 62% are in agricultural zones, 16% are in forest zones and 11% are in mixed farm and forest zones, according to the Department of Land Conservation and Development. The remainder are in rural residential zones.

“The farmland seems to be getting developed at a faster rate than the other categories,” said Sarah Marvin, a senior planner with DLCD, during a Nov. 20 hearing before the House Agriculture and Land Use Committee.

Oregon voters passed Measure 49 to amend another ballot initiative approved three years earlier, Measure 37, which allowed landowners to seek waivers of land use regulations imposed on their properties.

Landowners could also seek compensation for lost property values under Measure 37, but most counties could not afford to pay those claims and instead opted to waive restrictions on development — stoking fears of major new subdivisions that would interfere with agriculture and forestry.

Under Measure 49, those development rights were scaled back so that most landowners could only build three homes per property, or up to 10 homes if they could sufficiently prove that regulations reduced their property values.

Roughly 4,200 new parcels were approved by Oregon land use regulators under Measure 49, but only 1,700 parcels were actually created — leaving about 2,500 new parcels that could be created in the future, according to DLCD.

In areas such as Southern Oregon, the possibility of development occurring outside urban growth boundaries may raise the chances that newly built homes will be prone to wildfire hazards, said Marvin. “A lot of Measure 49 homes sites are going into extreme fire risk areas.”

To mitigate the risks from such home-building, DLCD enacted rules in 2014 under which landowners in farm and forest zones can transfer their development rights to rural residential zones or areas that have already been largely subdivided.

Since then, however, not one county government has implemented an ordinance that would allow landowners to transfer these development credits, Marvin said. That’s likely because county officials have limited time and resources to create such programs.

“They’d have to compete with other things on their agenda to get this in,” she said.

If landowners were excited about transferring their development rights, they’d probably demand that county officials make that option available — something that clearly hasn’t happened, said Jim Johnson, land use specialist with the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

“There’s not, in my opinion, a real demand for it,” Johnson said. “If nobody is asking for it, the county has other things to do.”

While the development credit transfer system should be a “win-win for everybody,” it’s likely that Oregon’s program is too restrictive to be enticing to landowners, said Dave Hunnicutt, president of the Oregon Property Owners Association.

Landowners are unlikely to want to jump through the program’s regulatory hurdles without an incentive, Hunnicutt said. “There’d better be something valuable at the end of that.”

Currently, development credits can only be transferred within the same county, which is a geographical limitation that probably discourages landowners, he said.

Those in remote rural counties would be more interested in the program if they could transfer the development credits to more urbanized areas, Hunnicutt said.

Allowing more flexibility makes sense, since geographical restrictions won’t prevent property development under Measure 49.

“Those are going to happen and there’s nothing anyone can do to stop them,” Hunnicutt said.

Another possibility could be to allow additional dwellings to be built with the development credits if they’re transferred from farm and forest land into rural residential zones, said Rep. Brian Clem, D-Salem, who chairs the House Agriculture and Land Use Committee.

“I feel like we need to sweeten the pot somehow,” Clem said.