Oil trains in the Gorge: Are we ready for a spill?

Published 1:17 pm Thursday, March 14, 2024

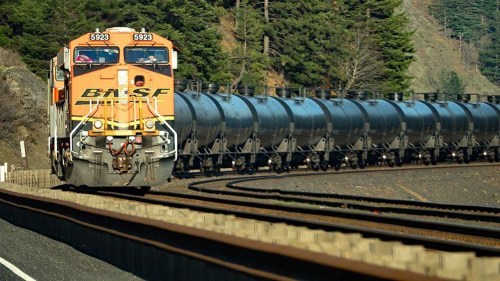

- An oil train rumbles through the Columbia River Gorge. Many residents believe another derailment is inevitable in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, an 80-mile-long stretch shared by Oregon and Washington.

THE DALLES — Wasco County Sheriff Lane Magill was among the first to receive the report shortly after 9 a.m. on June 13, 2023, of an event everyone in the Columbia River Gorge dreads.

An oil train with 23 tank cars carrying 540,000 gallons of crude oil had derailed near the confluence of the Columbia and Deschutes rivers in Oregon. Crude oil was gushing into the Deschutes and threatening the Columbia.

Magill took stock of his on-duty staff — top to bottom, deputies to office staff — then started mentally checking through tasks set out under the National Incident Management System.

“We determined who the incident commander was going be, that falls under NIMS, and we just rolled right into that,” Magill said of the episode last summer. “We all moved into our own spots.”

If you’re wondering why you haven’t heard of a major oil spill in the Columbia and Deschutes last summer, it’s because it never happened.

The imaginary “report” Magill and others received was part of a two-day “discharge train derailment scenario” emergency response drill held at the Fort Dalles Readiness Center in The Dalles.

The multi-agency simulation — which included more than 150 people from federal, tribal, state, county and municipal agencies, and BNSF Railway — is a legal requirement in Oregon per a 2019 law that requires railroads that transport oil to prepare and practice spill response plans.

Part of the goal was to refine Oregon’s mandated Geographic Response Plan to a train derailment.

The first day was a tabletop exercise in which agencies reacted on paper to the fictitious incident scenario and broke into different groups, such as logistics, planning, finance and operations.

“It’s not laid back,” Magill said. “Maybe people make an assumption when we have these types of exercise, ‘Oh, it’s just a bunch of government officials sitting around a table eating donuts and drinking coffee.’ But when you walk in that room you better be ready to go. We have the mindset that this is actually happening. You have to think that way because if you don’t you’re already behind the eight ball.”

The second day was a field deployment exercise.

“The Geographic Response Plan helps responders immediately assess an incident location and tells them, for instance, what kind of fish, birds or endangered species are in that area,” says Sheridan McClellan, emergency management services manager for Wasco County, who also participated in the exercise. “Wherever an incident happens, responders can open up the plan and find (pre-determined) strategies for each area, such as where to place booms for collection points based on the flow of the river in certain spots.”

Though it was Oregon’s first large-scale training exercise designed to help the state better prepare for a major oil spill from a railroad, the June 2023 exercise was just one of multiple drills that have become commonplace in the Columbia River Gorge since 2016, when a train traveling through the Gorge actually did derail and spill crude oil in Mosier.

Many residents believe another derailment is inevitable in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, an 80-mile-long stretch shared by Oregon and Washington.

“It’s not a matter of if trains are going to derail again, it’s where and when,” says former Mosier mayor Arlene Burns.

‘Russian roulette’ on the Columbia

On June 3, 2016, a Union Pacific Railroad train carrying crude oil derailed and caught fire in the Columbia River Gorge community of Mosier, a town of fewer than 500 residents about 70 miles east of Portland.

Traveling at 24 mph, 16 oil tank cars jumped the tracks some 800 feet from the river, spilling thousands of gallons of Bakken crude oil.

Three rail cars burst into flames. Firefighters worked for 14 hours to put out the blaze.

But for a rare lack of wind that day, the entire town could have been engulfed. Average wind speed in the Columbia River Gorge, where steep walls act as a funnel, is 10 mph, and sustained winds of 20 mph or faster are common.

“Lack of wind was the reason Mosier and everything to the east wasn’t wiped out,” said Burns, who was Mosier’s mayor from 2015 to 2022. “Our entire city limits were in the blast zone had there been an explosion.”

According to the EPA, only a “minor amount” of oil reached the Columbia River. The agency calculated that of the 47,000 gallons of oil spilled, 16,000 gallons burned or vaporized; 13,000 gallons collected in a nearby wastewater treatment plant; and 18,000 gallons discharged to soil.

The Mosier derailment was a wakeup call for officials responsible for disaster response in the Columbia River Gorge.

Federal, state and local agencies say they’re now better prepared to respond to unexpected incidents.

But the risk of another derailment remains.

And though oil train traffic has decreased in recent years, the number of cars carrying crude oil through the Columbia River Gorge more than doubled in the years following the Mosier spill.

What’s more, spring and summer months mark the height of train traffic on both Washington and Oregon tracks. These months also coincide with peak wildfire danger, creating the possibility of a train derailment causing a wildfire with exponentially greater risks of destruction.

“I’ve been living in the Gorge for 30 years,” says Burns. “The last 10 years every summer is just like Russian roulette if our town is going to burn down from a fire. It was never like that before. The hotter days have gotten hotter, the periods of hotter days have gotten longer.”

Crude rules

Prior to 2012, rail transport of crude oil through the Columbia River Gorge was virtually non-existent.

That year, however, volume surged — eventually reaching 60 million gallons per week — thanks to increased fracking of oil and gas from the Bakken Formation, a vast rock expanse in North Dakota.

For railroads, the Columbia River Gorge emerged as the go-to route to move oil from producers in North Dakota to refineries in Anacortes, Cherry Point, Ferndale and Tacoma, Washington, as well as California.

“Crude by rail is shifting to the West Coast in a big way,” wrote RBN Energy, an energy market analytics firm, in a 2013 blog post. “As the crow flies the distance from North Dakota to Washington State makes the Northwest a closer refining center than the East Coast.”

As the only sea-level crossing through the Cascade Range, the Gorge quickly became what critics call “a superhighway for fossil fuel transport.”

Lawmakers took note.

Following the July 2013 Lac-Mégantic rail disaster — when a 73-car Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway train carrying Bakken crude oil derailed in the Quebec town, killing 47 people and destroying the downtown area in a massive inferno — legislators in Washington directed the state’s Department of Ecology to create rules targeted at the two major railways operating in the Columbia River Gorge: Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), which operates on the Washington side of the Columbia River Gorge, and Union Pacific, which operates on the Oregon side.

The new rules required the railroads to provide the state with emergency plans and proof they have the financial resources to respond to a derailment. The Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission also began inspections on railroad crossings located on crude oil routes every 18 months and documenting incident data.

With a major push from environmental advocates, Oregon adopted a law in 2019 requiring railroads that own or operate high hazard train routes to have oil spill contingency plans approved by state’s Department of Environmental Quality.

Oregon’s “spill bill” put railroads hauling crude oil or liquefied natural gas under the purview of the state’s oil spill planning program, established fees of up to $20 on each oil tank car entering Oregon or loaded in the state, plus a small annual fee on railroads’ gross operating revenues in Oregon.

The fees help fund Oregon DEQ’s work, including the creation of two rail planner positions within the agency.

How about no crude at all in the Gorge?

The Yakama Nation was one of the first governments to respond to the 2016 Union Pacific derailment in Mosier, bringing resources from its environmental program.

Even before the accident, however, the Yakama Nation and other Tribes opposed the transportation of fossil fuels through the Gorge.

“We should not have any fossil fuels coming through our ancestral homeland, especially along the river,” said Austin Greene, tribal chairman for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, after the 2016 Mosier derailment.

“We’ve been a very strong advocate of the fight of a fossil fuel superhighway coming through this Columbia River Gorge,” said JoDe Goudy, chairman of the Yakama Nation at the time of the Mosier incident.

Tribes argue that transporting toxic materials through the Columbia River Gorge impacts natural and cultural resources. They want trains re-routed.

But they aren’t alone in wanting crude oil train operations curtailed in the Gorge.

In 2019, Wash. Gov. Jay Inslee signed a bill that allowed the state to turn away trains not meeting state-sanctioned vapor pressure thresholds — a measure aimed at reducing the volatility of transported crude oil.

In 2020, however, the Trump administration blocked the Washington law, saying the state was illegally attempting to dictate the commodities other states can transport to market.

“A state cannot use safety as a pretext for inhibiting market growth or instituting a de facto ban on crude oil by rail within its borders,” wrote Paul Roberti, chief counsel of the Transportation Department’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

Montana Attorney General Tim Fox called the court decision “a victory for … oil-rich states.”

The decision coincided with an all-time high for crude oil train traffic in the Gorge, nearly 115,000 cars in one year.

In lieu of a total ban on crude oil trains, many residents think more could be done to ensure future safety.

Burns would like to see trains travel at slower (i.e., safer) speeds through the Gorge. And for railroads to implement seasonal shipping measures.

“Couldn’t we find a way to ship crude oil for the eight months of the year when it’s moist and rainy and not have that oil shipped at a time when there is tremendous fire danger?” she says. “That would enable us to feel a lot safer.”