Homeplace: Nate Paulson is gone, but his gifts remain

Published 5:30 am Tuesday, August 6, 2024

- Nate Paulson died in 2010 at the age of 33. His death prompted his family to promote suicide awareness, an effort they continue to this day.

The whole time I’ve known Nate Paulson, he’s been dead.

But, for reasons I can’t explain, very much alive.

Nate’s with me on the hard projects and difficult stories. In 2022, I reported on local neurosurgeons who hurt a lot of people. The calls from those folks, or their surviving families, came so fast and hit so hard, I needed Nate’s photo up on my monitor to keep typing the tragedies.

Nate died 14 summers ago. He left behind a healthy marriage, toddler son and promising career. The 33-year-old took his life in a carefully planned suicide in a garage storage room at his home.

Safely away from his tiny son’s eyes and where the act wouldn’t taint the rest of the home. It was Nate’s last gift.

As with most such deaths, none of it made sense. Nate craved life, he was rich in friendships, his family loved him deeply and he loved them back.

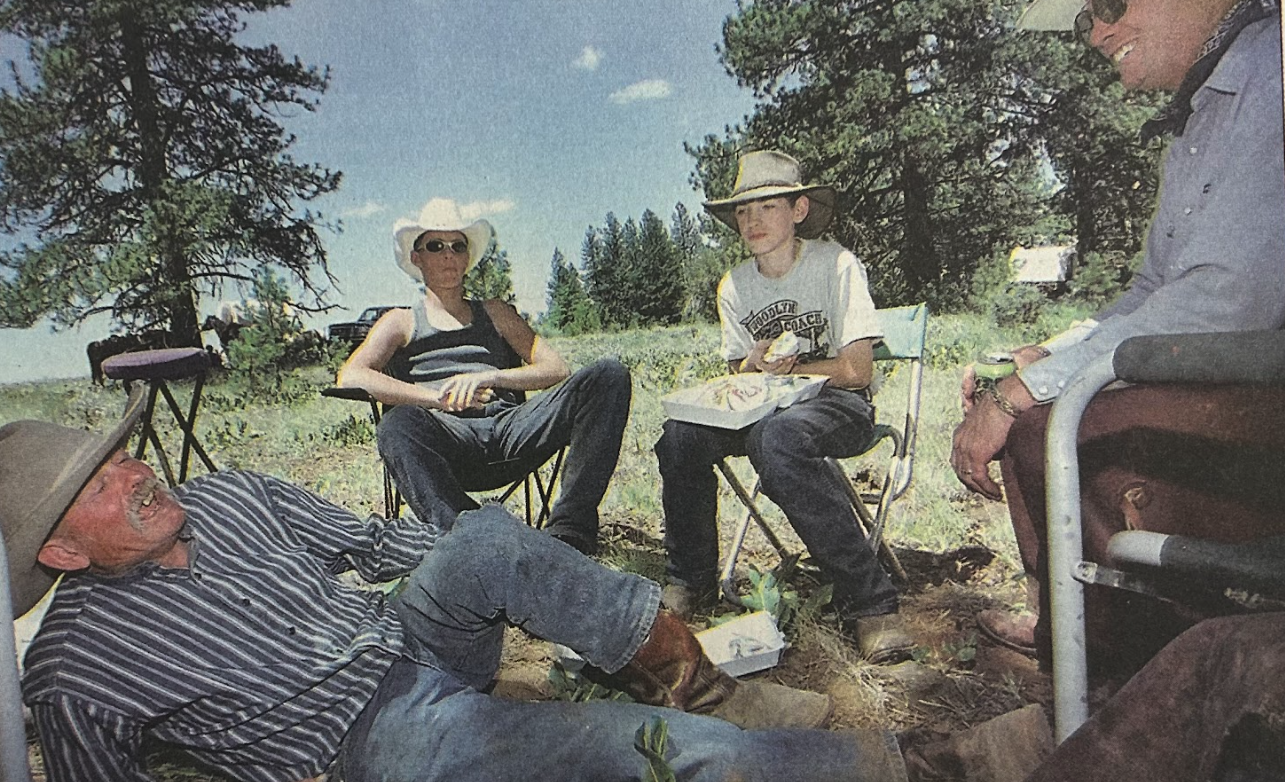

He’d climbed mountains, kayaked in lakes, fished the rivers. The autumn before, Nate hiked Mount Rainier, fulfilling a dream.

“Who could have guessed,” his father, John Paulson, said in 2011, “that nine months later he would kill himself?”

More than one thing can be true at once. Nate struggled with pieces of his life. He didn’t like to focus on himself, no matter how low he was. Nate could be too sensitive for this world. Depression claimed squatter’s rights at times, refusing to move out.

Courageously, Nate armed himself through therapy and fought off the darkness. Until he couldn’t.

I would meet Nate’s father seven months afterward, at a time of unprecedented suicide numbers in the Walla Walla area. The county coroner called, urging me to convene a roundtable to address the situation. I’m not sure who asked John Paulson to come, but there he was, his eyes reflecting the devastation of his boy’s recent death. His shoulders visibly bore immense sadness.

I so did not want to go to his house to learn about Nate; I didn’t believe I had skills to capture the angst or grit to swim in such sadness.

I went, though, and began writing the series, “Suicide on our doorstep.” Two weeks were filled with interviews, studying the language of suicide reporting, losing sleep.

Then the stories were told, guidance given, help offered. A support group for suicide survivors was born. We’d sounded the alarm.

But something happened that doesn’t, usually — John and I became knit together by Nate.

This isn’t woo woo stuff. You’ll rarely find someone more skeptical of myth than a reporter. But I can’t say what it is, either.

John gave me a photo of Nate as I wrote his story. I needed that kind of connection, to look at this young man and talk to him. I’ve used this method for decades when reporting heartache.

I didn’t file Nate’s picture, him in his Patagonia shirt in his Patagonia office, afterward. It stayed taped on the corner of my computer. I kept talking to Nate in the hard times.

I began telling John about the days I could feel Nate with me. In return, John unpeeled the layers of his son for me.

We spoke of other things, too. John was so happy when Camo Man asked me to marry him later that year. I was sad when The Paulsons moved across the state, knowing the hole they left in our community.

We’ve discussed health care, houses, pets, grandchildren, aging.

I tell John I value his friendship, his heart. He tells me our relationship has become woven into the fabric of his son’s life — the loss, recovery and rejoicing.

“We’ve walked this road together. You couldn’t plan this friendship, you can’t will it. I count it as a gift from Nate’s suicide,” John said.

Nate the Great — his boyhood nickname — is here. His smiling face is next to the light switch in my office when it’s not propped in front of me.

The Paulson family continues to promote suicide awareness. There’s no choice but to turn dark into light as much as possible; this is a leading cause of death among young Americans.

A study just published through the Journal of the American Medical Association says research suggests only 40% of those young people who have died by suicide had a documented mental health diagnosis.

We have to begin looking sooner rather than later.

I urge you to read and act upon this difficult information. Because you might know a Nate. Or you will.

If you are in crisis, call, text or chat with the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988, or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

The JAMA report on suicide in America’s young people can be found at tinyurl.com/mr62u8ce.