Kobe Bryant’s Everlasting Influence

Published 5:43 am Thursday, July 13, 2023

- Kobe Bryant’s Everlasting Influence

The August 2023 issue of Sports Illustrated features The Power List, the definitive index of the 50 most influential figures and forces who drive the sports world, on and off the field and court. For more on The Power List’s Icons and Leaders, like Kobe Bryant, click here.

Skylar Diggins-Smith met him—her primary mentor/inspiration/idol/most improbable friend—at a commercial shoot. They filmed the spot in 2013, after her star turn at Notre Dame and before she became a WNBA mainstay.

Nike sponsored her, same as him, which is how both arrived in the same place, on the same set. Eventually, she mustered the courage to approach him, this basketball deity, beloved throughout the world. She asked for a photo, starstruck; her favorite picture, even now. And yet, while her hero understood what he meant to other people, he didn’t act like he knew that his presence filled hearts and weakened knees.

“He was Kobe and he was just Kobe, if that makes sense,” she says. “He didn’t try to be anybody else. He was real, genuine. Him.”

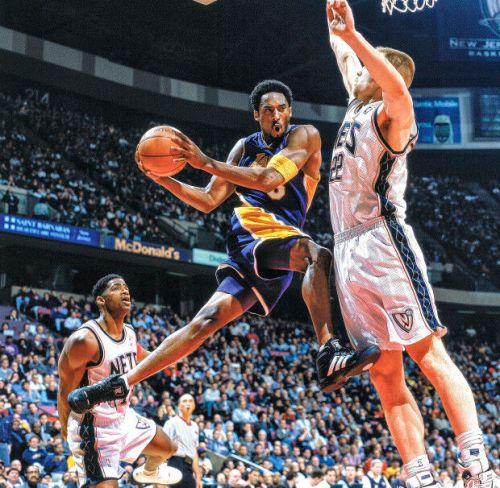

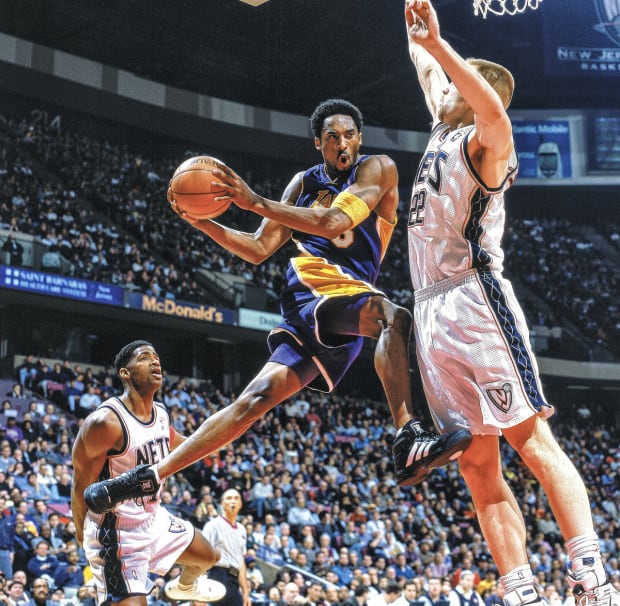

Kate Frese/NBAE/Getty Images; Barry Gossage/NBAE/Getty Images

That Diggins-Smith refers to Kobe Bryant the same as the rest of the world, by his first name, no additional identifiers necessary, speaks to his impact, its depth. She’ll never forget that day. Nor will she forget Jan. 26, 2020, a Sunday, the worst day, when Bryant; his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna; and seven others died in a helicopter crash. It took Diggins-Smith years to understand, let alone explain, the significance.

Bryant wasn’t just a five-time NBA champion, Hall of Famer and all-time great; Kobe spread basketball. But he also, specifically, spread women’s basketball. He called Breanna Stewart after she ruptured her Achilles tendon to offer guidance on an injury he understood too well. He wore WNBA gear, proudly and in public. He founded the Mamba Sports Academy, which provided access to sports for girls and other children. “In our game, no one had more impact,” Diggins-Smith says. Each female player saw in him the title of his book, The Mamba Mentality. Each also saw that mentality in themselves.

They weren’t alone. Kobe wrote TV and commercial scripts. Kobe produced documentaries. Kobe read Harry Potter. Kobe befriended regular folks, writers, directors, celebrities. Kobe woke up early, tried new things, excelled at everything. Kobe challenged himself, in basketball and outside it, impacting people in numerous industries, various countries and different economic stratospheres along the way. His death, Diggins-Smith says, forced everyone influenced by him to reach deeper and push for more, and Diggins-Smith believes that stems from the rare duality baked into Kobe, part of his genetic code. He was the most savage competitor in sports at least since Michael Jordan retired. But he was also the most relatable celebrity alive.

She sighs over the phone, perhaps to acknowledge that she would gladly exchange every ounce of impact for Kobe, in the flesh. This is the next-best alternative: “Kobe is everywhere, you know, and that means something.”

Before the 2018 football season, Kobe popped by the Alabama campus for a visit. This was August, only months removed from The Benching—when Nick Saban swapped Jalen Hurts for Tua Tagovailoa at halftime of the national championship game. Tagovailoa would remain the starter. Kobe’s message was intended to resonate with both, with all.

Hurts sat in the audience, up front, as Bryant addressed the Crimson Tide. Everyone always asked him for his secrets, Bryant noted. There really wasn’t a secret at all. Just editing. “I learned at an early age, I have to edit my life,” he said. “If there’s s— that’s bad for me, if there are people that are bad for me, I have to edit . . . them . . . out of . . . my life.”

The message resonated, with Hurts especially. He had crafted a plan for the rest of his career—serve as an elite backup if he never regained the starting role; make the most of any spot duty; graduate, in part to open up transfer options; excel; NFL; world domination. Kobe’s message provided one final push. Hurts stuck to his plan. When Tua hurt both ankles in the SEC championship game against Georgia, Hurts came in and sparked a comeback. Same field as the benching. Same opponent. An edited life . . . won.

Hurts transferred to Oklahoma, made the NFL, continued editing and, amid an MVP campaign last season, pushed Philadelphia to the Super Bowl. His sports performance director in Philly, Ted Rath, had visited Alabama’s campus in 2020. He learned about the speech back then and huddled with Hurts as Super Bowl LVII approached. Both decided they would use it.

On Day 1 of Super Bowl week, Rath stood before the team inside their temporary weight room in Arizona. In the hopes of tying everything together—the goal ahead, how Hurts approached recovering from far more shoulder pain than the public knew—Rath hit play on his laptop. Kobe’s speech boomed across the room.

Rath found Hurts afterward. Hadn’t that been the point of their last month together? Not listening to agents, relatives nor friends. Missing two games he desperately wanted to play in. Looking deeply inward. Focusing on recovery, nothing else. Editing his story and, by extension, the story of the Eagles’ season.

“I see a lot of Kobe in Jalen,” Rath says. The quarterback led his fired-up team out of the weight room on that day in Arizona, everyone floating onto the practice field. Six nights remained before the Super Bowl. The Eagles, players say, had their best practice of the season.

Hurts is still editing, studying Bryant’s evolution as a leader. Rath looks at Hurts and sees Kobe. How many other trainers could look at their superstar and say exactly the same thing?

Diggins-Smith subscribes to a theory that the greatest of the greats, like Kobe, have their impacts widen after death. She sees it at basketball courts across the country, in bolstered WNBA resources and interest, in so many children named Kobe or Koby or Ko-B.

Like Coby Bryant. Before helping to lift Cincinnati into the upper echelon of college football and before the Seahawks made him a prominent part of their defensive overhaul, he was a baby whose family loved the NBA. Sure, Ronnie Bryant lived in Cleveland. But it wasn’t LeBron James who most inspired him. It was Kobe. So when it came time to name his youngest son, Ronnie decided to pay homage to his favorite player. (There is a mild family dispute. Coby says his older brother, Christian, claims he came up with the name. At age 7! “Older brothers always want to take credit,” Coby says with a laugh.) Regardless, the originator changed the spelling on purpose, so that Coby could shape his own legacy in Kobe’s image.

What’s in a name? A lot, Coby Bryant learned. Try playing basketball, even in youth leagues, when your name is Coby Bryant. Try watching clips of the NBA superstar you’re named after when you’re 7, to understand the standard you must meet. Try buying school lunch and having a clerk ask for your ID, because they don’t believe that name is your name.

Eventually the significance seeped into young Coby’s soul. He embraced the Mamba Mentality and took that approach into football. As a senior, he won the Jim Thorpe Award. Before Cincinnati competed in the kind of game it never reached—a CFP semifinal against Alabama—Coby switched his jersey number from 7 to 8. More homage.

When he was drafted in the fourth round in 2022 by Seattle, Coby immediately took 8. Then he went all Kobe, injecting the soul of the athlete he’s named after into a defense (and team) that far exceeded expectations. Coby says that Kobe came up all the time. Like when the defensive backs discussed the full nature of their lives (Coby, for instance, played baseball growing up, and focused on his degree in interdisciplinary studies while in college). Or when they talked about their futures (Coby wants to enter broadcasting—like Kobe, becoming a member of the media). Or whenever someone pointed out the expectations for the Seahawks (low) and how they might overcome them (work). “It’s no pressure,” Coby says. “It’s a privilege.”

Hence his rookie season: six starts; a shift inside, to nickel corner; gradual improvement; and four forced fumbles, tied for third in the NFL. All these seamless adjustments started in the same place, with the same person. Or people. Coby. And Kobe.

“I try to carry that mentality,” Coby says. “That’s the best way to represent.”

Diggins-Smith Knew the perfect way to honor Kobe. Hence the jersey—his No. 33 from Lower Merion High—she wore to a game in July 2022. But she also knew, “You gotta be careful,” when wearing one of Kobe’s jerseys to the office, especially when that office is a basketball court. Not to worry. Playing for the Mercury, she dropped 35 points.

“You put that jersey on, and you feel like you’re in Space Jam,” she says. “Everything comes to life. It’s like, O.K., I got that power. Whoever got me, got problems.”

Even on that day, memorable as it was, she understood something else, something even more powerful. Simply honoring Kobe on the basketball court wasn’t nearly enough. Kobe’s influence made her a better mother. A better teammate. A more empathetic person. A more well-rounded one.

Months passed. Then years. She watched his Hall of Fame induction in May 2021, her television screen yet more proof of how many Kobe impacted. There were young women in the crowd. Old men. Kobe’s widow, Vanessa. Basketball luminaries. Movie big shots. Writers, producers, creators. She wished only that Kobe could have seen it, could have spoken.

“He was bigger in person,” she says. “Tall, big personality, that presence.”

He’s even bigger now, in death. Gone too soon. But still filling the sports world, the world, with deep purpose. Still Kobe. Still influencing.

Because of Kobe, in part, Diggins-Smith produced a documentary series for Nickelodeon. Because of Kobe, in part, she continued to refine her professional basketball career. Because of Kobe, in part, she pursued more Olympic glory. And because of Kobe, in part, her decision to step away from part of a WNBA season, her 10th, closer to the end than the beginning, was easy.

She had a baby girl, who may play basketball. Kobe taught Diggins-Smith many things, but if he taught her only one thing, it was this: to embrace life, all of it, in search of balance and greatness and passions, plural. “He forced everyone to look deeply inward,” she says. “To ask: How can we do our part?”

This is how. By loving basketball and family. And by supporting that baby girl, in whatever she decides to do, as long as a certain mentality is the benchmark, the standard, the soul.