New report finds firearm injuries leading to emergency department visits spiked since 2019

Published 12:00 pm Tuesday, November 8, 2022

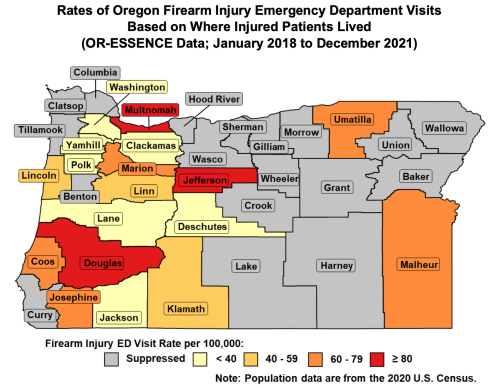

- The number of firearm injuries that led to emergency department visits by county per capita in Oregon, January 2018 to December 2021.

PORTLAND — A new study calls firearm injuries that lead to emergency department visits in both urban and rural Oregon a “public health crisis that continues to grow at an alarming rate.”

Oregon Health & Science University and Portland State University School of Public Health on Oct. 20 announced the report, “Firearm Injury Emergency Department Visits in Oregon, 2018-2021,” which shows emergency department visits due to gunshot wounds increased from 459 in 2019 to 837 in 2021, nearly doubling in the span of just two years.

Trending

Broken down county by county, the report illustrates that although counties in the western part of Oregon, such as Douglas and Multnomah, experience the highest rates of per capita firearm injuries leading to emergency department visits, Eastern Oregon counties such as Umatilla and Malheur are not far behind.

Umatilla and Malheur counties were placed in the second-highest of five categories for per capita firearm injuries leading to emergency department visits at 60-79 visits per 100,000 residents.

“By raw numbers alone, the highest numbers of individuals with firearm injuries appear in the more populous counties,” explained Kathleen Carlson, director of the new Gun Violence Prevention Research Center at OHSU and co-author of the study. “But because the population is low relative to western counties, it shows when we compare individuals in East Oregon counties on average have a higher risk.”

Carlson said several factors were involved in the spike in gunshot wounds since 2019, but the causal factors may look different between urban and rural communities.

“Our research, in general, has shown there are more self-harm injuries in the rural parts of our state, but in rural parts of America, too, as opposed to interpersonal violence,” Carlson said. “It isn’t 100%, but we know self-harm and death by suicide are more frequent rates-wise in rural counties.”

Local law enforcement’s takeThe chiefs of police for Hermiston and Pendleton expressed their views on the effects of this violence and the injuries it produces.

Trending

“We are experiencing more violent people,” Hermiston Police Chief Jason Edmiston said. “This is evidenced in both an incredible increase in aggravated assaults and the fact we have experienced more violence against our officers. We currently have an officer out with a torn bicep that took place and was intentional on the part of the suspect back in July. That officer is hopefully going to be back before the end of the year.”

Aggravated assaults for the first nine months of this year as compared to last year in Hermiston are up 120%, from 15 in 2021 to 33 this year.

“Our total crime is up 29%,” he said. “And though our violent crime experience has been relatively small as compared to property crime, we are seeing a 45% increase from last year. Of the four violent crimes — homicide, rape, robbery and aggravated assault — three categories are down, but that huge increase in aggravated assaults skews the numbers up.”

Pendleton Chief of Police Charles Byram said his department has seen an uptick in firearms possession offenses.

“Our officers are finding more firearms on people that shouldn’t have them,” Byram said, but added, “I can count on one hand the number of times we’ve had to respond to a firearm-related injury in the last year. Two or three at the most is what we’ve responded to. Normally those are accidental shooting-type things.”

Study shows disparityNo clear-cut solution

To effectively respond to this emerging public health crisis, the report suggests a comprehensive approach to recognize the full breadth of the problem and public health disparities that affect the causes and consequences of firearm injury. While the report offers data-backed prevention and risk reduction strategies, a clear-cut solution has yet to emerge.

“These are all pieces of a thousand-piece puzzle, but we have a thousand possibilities for making it better,” Carlson said. “Our next step as researchers is to work with this data and the other sources we have and start to hone in on causal factors. When we’re just looking at rates, per capita rates, numbers and trend lines, it gets us some clues about what’s happening, but really it’s hard to say, ‘Umatilla County, here’s what you need to do.’ Maybe we’ll be able to do that better as we continue to collect data.”