Oregon State Hospital may face admissions limits

Published 8:21 am Tuesday, August 16, 2022

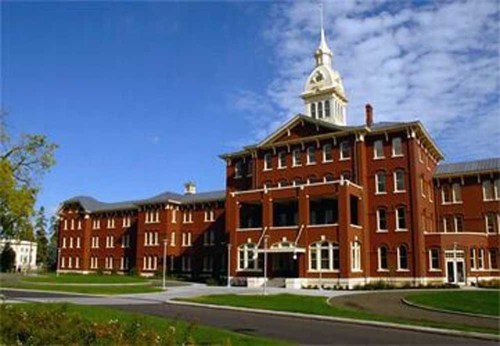

- The Oregon State Hospital in Salem.

More than 70 people in Oregon jails who need mental health treatment are waiting for Oregon State Hospital beds.

Now the state’s biggest disability advocacy group and public defenders are calling for a federal court to place strict limits on admissions, to free hospital beds faster and keep people accused of crimes but in need of help from languishing in jail. The limits, if imposed, would restrict the types of patients who may be allowed in and how long they can stay.

Disability Rights Oregon and Metropolitan Public Defender, the two groups, on Monday urged U.S. District Judge Michael W. Mosman to require the hospital admit only patients found unable to aid and assist in their own criminal defense, those who have been found guilty of crimes except for insanity, and people outside those two categories who have been deemed dangerous to themselves or others.

The organizations also called for the Salem hospital to limit patient stays to no more than 90 days for those accused of misdemeanors, and generally no longer than six months for those accused of felonies.

State hospital spokesperson Amber Shoebridge said the hospital’s parent organization, the Oregon Health Authority, was not opposing the motion.

The move comes on the heels of a court-ordered review of the hospital’s admissions policies earlier this year, conducted by Michigan-based mental health expert Dr. Debra Pinals.

Pinals’ 35-page report from June recommended that the hospital gradually lower its average wait times for patients, aiming for 22 days or fewer by the beginning of this month, and 11 days by January. She recommended that by Feb. 14, 2023, the hospital should be admitting patients within seven days, which would put it back in compliance with a 2000 federal court order.

But the hospital is far from that goal.

“What we’re asking the court to do in this motion is supersede state law, and put limits on how long someone can stay at the state hospital,” said Emily Cooper, the legal director of Disability Rights Oregon.

The hospital is trying to move patients into community care by more frequently reviewing patients for release, she said. The average wait time for a patient is about 40 days, Cooper said. Shoebridge confirmed 73 people this week are waiting for admission.

If the judge grants the request, the hospital will begin staggering the release of about 100 patients who are ready for discharge over the next six months, Shoebridge said.

“Today’s motion could allow patients to be admitted to OSH faster and yet will have significant impacts on patient care and treatment in the hospital and broader community,” Oregon Health Authority Director Patrick Allen said in a written statement Monday.

A hospital representative did not immediately clarify what impacts Allen was referring to.

Cooper said the state has also increased its funding of community mental health facilities, which would allow people to be treated locally instead of in Salem. But while some counties have opened up new beds, Cooper said staffing those facilities is still a challenge.

Pinals’ investigation was prompted by two federal lawsuits. The first, filed by Disability Rights Oregon in 2000, mandates the hospital admit criminal defendants whose poor mental health means they can’t aid and assist their attorneys no more than seven days after they’re lodged in jail. A federal judge in May 2020 modified the order to accommodate the state hospital’s limited admissions policy, intended to reduce COVID-19 outbreak risks. But Disability Rights Oregon disputed the ruling, saying it violated people’s constitutional rights.

And in November 2021, two people in Multnomah County who were found guilty of crimes except for insanity sued the hospital, saying they were waiting in jail for six months, despite being ordered to get state hospital treatment.

Cooper said there is a concern that the proposed change, which would discharge patients more quickly, could send people back into the cycle of the criminal justice system.

But she hopes recent investments from the state will help change that.

“We already have a revolving door,” she said. “The key to stopping that is fully funding the continuum of mental health resources.”