A ton of trouble: Bullfighters put themselves between the bull and the rider

Published 1:00 pm Monday, July 18, 2022

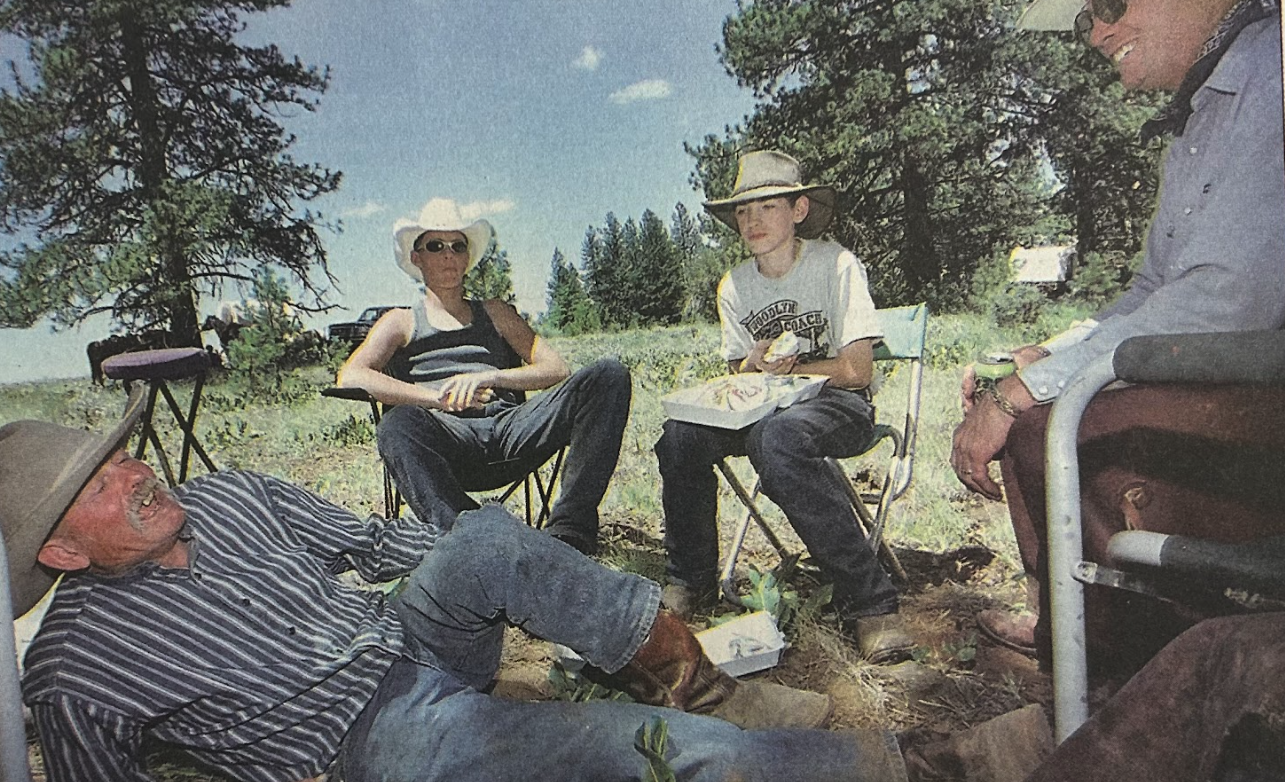

- Bullfighter Danny Newman, right, waits for his chance to help a rider during the bull riding competition Saturday, July 16, 2022, at the Baker County Fairgrounds.

Jackal Crenshaw’s job is to insert all 165 pounds of himself between one ton of energetic bull and the person who was, until recently, on its back.

In bull riding, the action begins when the chute, or pen, opens and the bull bucks into the arena.

The ride ends when the competitor, even if he has made it the full eight seconds, has to get off the bull and, for at least a few seconds, becomes defenseless.

Protecting the rider during that perilous period is something that Crenshaw said, about half an hour before he’s ready to start his daring act, “is not supposed to be done.”

He talked about the danger, and the exhilaration, while sitting in his Honda sedan, applying red paint to the tip of his nose in the minutes before the annual Baker City Bull Riding competition on Saturday evening, July 16 at the Fairgrounds arena.

Crenshaw is a bullfighter.

But his job doesn’t involve any fighting, in the sense of a physical exchange between him and the bull.

Although in some cases the bull will make contact with him — as happened during Saturday event, when the horn of one bull “xylophoned” his ribs.

Crenshaw sums up the gig as simply “saving cowboys.”

On Saturday, Crenshaw and his fellow bullfighters, Matt Akers and Danny Newman, worked in coordination to distract heated bulls from downed riders with the goal of preventing injury to the rider, the bull, or themselves.

Unlike the bull riding event — and unlike other forms of bullfighting involving swords and matadors or freestyle bullfighting — this crew wasn’t competing in any way.

Akers, a 36-year-old who’s been bullfighting for 13 years, said that even though the fighters try to draw the bull’s attention to themselves, the job isn’t about being a “showboat.”

“We stay quiet when we have to be,” Akers said. “You could be running out there and make rounds when you don’t have to, and you could have a situation where you bring the bull back to the bull rider because you are just focused on that bull.”

The fighters never engaged with the bulls until necessary — often, the bull would buck or run its way out of the arena on its own. Only when a bull moved toward a rider would the fighters step in.

How to head off a bull

Akers said the trio used what he described as a Northwest style of bullfighting, which involves using a tactic called “head and tailing” — one fighter entices the bull forward while another hovers around its backside, causing the territorial beast to spin in circles, unable to pick one target.

They might sometimes stay quiet, but the fighters are hard to miss.

Each wore a long-sleeve shirts with bright red markings to catch the eye of the bull, and two fighters — Crenshaw and Newman, who’s 51 — wore traditional loose-fitting denim skirts, called baggies, which allow the bull to make contact with cloth instead of the skin and bones of the fighter.

The fighters all wear protective vests and some form of a hockey girdle, also for protection.

And to complete the outfit, Crenshaw wears clown-like face makeup to accompany his waxed blonde mustache, carrying on the tradition of when bullfighters also served as the entertainment during the down time of rodeos.

Crenshaw, despite being the youngest of the three fighters at 24, said he likes to “keep it old school” with his outfit.

While most everyone involved with the rodeo wore flat-bottomed cowboy boots on Saturday, the three fighters donned footwear with molded rubber cleats for traction.

The cleats help the fighters perform the quick, athletic movements necessary to evade charging bulls. Akers has a background in boxing and mixed martial arts, sports that require fast feet and movements in short bursts, as does bullfighting.

Crenshaw said that while he can’t outrun a bull in a straight line, he’s much more nimble than the bulky creatures. All he has to do is run on a curve, and even with the bull’s horns tailing inches behind his rear end, he’ll lose the animal.

Sheer athleticism allows the fighters to protect riders and themselves in many scenarios, but according to Akers, certain situations require a pre-calculated and coordinated effort.

When competitor Wyatt Covington fell from his bull during one of his rides Saturday, something unusual happened. Instead of hitting the dirt, his hand got stuck under the flat braided rope that riders use to hold the bull, leaving his body dragging on the ground while the bull attempted to shed the rider.

Getting the bull to spin in this case, as the fighters typically try to do, would have left Covington underneath the animal.

Instead, the fighters got the bull to “line out” or continue in a straight line. It wasn’t until all three yanked on the rope — that’s when the bull’s horn probed Crenshaw’s ribs — that Covington’s hand popped out, leaving him uninjured.

“I haven’t seen a guy get stuck that bad in a long time,” Akers said.

The frenzy might have seemed like a random scrum to some in the audience that packed the grandstand and bleachers, but Akers says that’s far from the truth.

“There’s a method to it, there’s a system to what we do,” Akers said. “You are making split second decisions and you’re executing those decisions to hopefully slip in there and protect a guy.”

“There’s a method to it, there’s a system to what we do. You are making split second decisions and you’re executing those decisions to hopefully slip in there and protect a guy.”

— Bullfighter Matt Akers