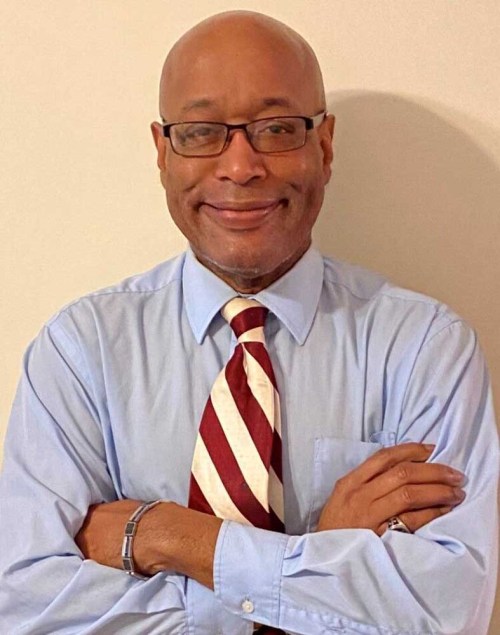

Director of Oregon police training agency resigns

Published 3:00 pm Friday, April 22, 2022

SALEM — Jerry Granderson, who the governor appointed to lead the state’s public safety certification and training agency in late March 2021, has abruptly resigned, partly over his objections to what he considered an unfair and improper evaluation of him recently by the agency’s board.

He resigned just days after he was placed on paid leave April 15, pending an investigation by the Oregon Department of Justice into allegations against him involving alleged discrimination and creation of a hostile work environment. He denies the allegations.

“I refuse to stay on paid leave and waste the people of Oregon’s money,” he said.

Granderson, 59, told The Oregonian he submitted a letter of resignation to the governor’s office on Sunday and the following day a similar letter to the chair of the board on Public Safety Standards & Training.

In his resignation letter, Granderson cited concerns about “counseling” he received Friday from the board over his recent “Director’s evaluation,” which included a reference to the state Justice Department investigation he faced.

He strongly denied any wrongdoing, and suggested in the letter that the complaint resulted from “disgruntled employees” who in his view have resisted “fundamental changes” he has attempted to put in place at the police training and certification agency.

Granderson was disturbed that his evaluation included a board member’s reference to the investigation, particularly because it hadn’t been completed. He argued it would “prejudice” his evaluation, which was set to be discussed April 28 at the board’s public quarterly meeting, before the conclusion of the Justice Department’s inquiry.

Granderson, who is Black, also wrote that he was informed there was concern among board members and staff that he was making promotions and hirings “solely based on race, gender and sexual orientation,” and “chasing out good employees.”

Granderson said he has been working to respond to a state audit about the lack of diversity in the agency and had commissioned his training administrator to research “how to ‘legally’ increase such diversity in the Training section,” given it is the least diverse at the department.

He said some staff have left the department due to COVID-19 safety mandates and other job opportunities and some out of animus toward reforms he’s tried to make, including changing the color of training academy students’ uniforms from all black to two colors to “eliminate the military-like appearance of our students” and restricting instructors who are not active police officers from wearing weapons while on the department’s campus.

An unidentified board member also complained that Granderson sometimes referenced the department as “my agency,” and several said they were concerned that Granderson hadn’t met regularly with them face-to-face outside of the board’s quarterly meetings.

Granderson said it’s insulting that he’s being questioned about referring to the department as “my agency” when executives statewide and nationally do the same when talking about the agencies they oversee. He said his calendar has shown he’s been trying to meet with police chiefs and sheriffs, lawmakers and civilian constituents across the state, though the pandemic made that more difficult last year.

“The one narrative that I agree with is that ‘it is too early to comment on my performance,’” he wrote in his resignation letter to the board.

“The board’s evaluation of me seems to be more based on whether I’m liked and maintaining the status quo or not,” Granderson wrote.

“I think it is obvious, however that when one is attempting paradigm shifts, there are some who will go at any level to resist that change and attempt to influence a board that has the power to determine my professional standing.”

Granderson said he resigned before the evaluation of his first year as department director was to be made public at the board’s quarterly meeting on April 28. He urged the state to ensure that policies or processes are altered so whoever fills his role doesn’t face the same “apparent political, emotional dilutions” in their performance evaluation.

Gov. Kate Brown selected the retired career FBI agent to lead the state public safety department. At the time of Granderson’s appointment last March, the governor praised his “blend of field training, program management and leadership experience,” in making him “uniquely suited” for the job.

Brown’s spokesperson Liz Merah said Wednesday she could not comment about the specifics of Granderson’s departure, citing an ongoing investigation. She said Granderson was placed on paid administrative leave Friday and subsequently submitted his letter of resignation over the weekend.

“Our office generally does not comment on matters of pending investigations or individual personnel issues,” Merah said by email.

Kristina Edmunson, spokesperson for the Oregon Department of Justice, said the department has hired a special assistant attorney general to help with an investigation. State Justice Department records show the state in mid-March hired the law firm of Michael V. Tom to advise the Justice Department and public safety standards agency about “workplace complaints,” conduct an investigation into those complaints, provide status reports to the Justice Department and a report outlining its investigation and findings. The law firm was hired at the rate of $325 an hour.

Granderson oversaw the department’s budget of more than $55 million and worked with the board to develop training and certification and licensing standards for more than 41,000 public and private safety professionals. His annual base salary was $162,216, according to the governor’s office.

Granderson came to Oregon after he worked for the FBI for nearly 23 years.

He was appointed during a time when police training and certification has come under heightened scrutiny amid a social movement to reform law enforcement in the wake of the May 2020 killing of George Floyd, a Black man who died after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck.

Granderson also oversaw the police training academy as it struggled to hold in-person instruction at its campus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Brian Henson, who has been the department’s acting assistant director under Granderson, said he started serving as acting director on Tuesday.

Henson, who does not have a law enforcement background, previously served as administrator of the agency’s operations and services division and has spent 20 years working at the department.

“All I know is he tendered his resignation to the governor on Sunday morning,” Henson said, adding that he did not know Granderson’s motivations. He said Granderson still has many personal belongings and documents in his office.

Henson called Granderson “dedicated to the agency and the criminal justice and fire professions that we support.”

“We have a dedicated team of professionals who work here and will continue in our mission,” he said.

Darren Bucich, the chair of the board on Public Safety Standards & Training, did not immediately respond to messages seeking comment.

In an interview in January, Granderson told The Oregonian that he was working to oversee the adoption of policing reforms recently approved by state lawmakers, including the creation of standards for conducting background checks for new police hires, and a statewide equity training program for police.

A state audit in December found that the department that certifies police officers gives too much deference to local police agencies to hold officers accountable for excessive force or other misconduct. The audit also found that narrowly defined state administrative rules hinder the ability of the state Department of Public Safety Standards & Training to revoke an officer’s certification.

In response, Granderson said he had told staff he wanted to see any file involving an officer’s alleged misconduct before the department moved to approve a so-called “administrative closure,” when it decides not to send a matter to the board to evaluate whether to suspend or revoke an officer’s police certification. He also lamented the lack of diversity among the department’s staff and said he wanted to work to see women make up half of the agency’s staff some day.

Granderson also said that more oversight and standards needed to be provided for police field training, which is usually done by each respective police department. The audit found that officers in each police department in the state vary in experience and training, and state administrative rules don’t require field training officers to receive any standard training.

In his interview about the audit with The Oregonian in January, Granderson said: “This is an agency that affects the people, and people want to know what’s going on. And that’s why I say this audit — I look at it as a roadmap to find out what’s wrong, what needs to be fixed, ask for the resources to fix it and make things better. I think one of the most dangerous things particularly at this time for the American people is the status quo. And the status quo will harm you. You know, we’re trying to go beyond the status quo and just make things better.”