Yellowhawk clinic brings first COVID-19 vaccines to children on reservation

Published 5:00 am Tuesday, November 16, 2021

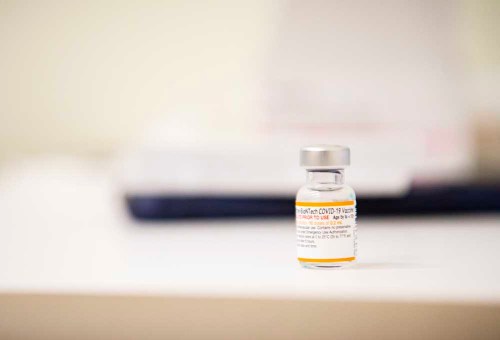

- A vial of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for ages 5 to 11 sits on the counter Saturday, Nov. 13, 2021, at Yellowhawk Tribal Health Center in Mission.

MISSION — Luka Worden sat between her parents in the waiting area at Yellowhawk Tribal Health Center, eager to become one of the first children vaccinated against COVID-19 on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

At least 50 children ages 5 to 11 were scheduled for the shot at the mass vaccination clinic on Saturday, Nov. 13 — the first day tribal health officials offered vaccines for youths.

“I wanna be safe and I don’t want to get COVID and I want a lot of people to get the vaccine so this will go away,” said Luka, a 10-year-old enrolled member of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe in Idaho.

Health care workers and families said they were thrilled to see children vaccinated at the clinic, noting the day as yet another milestone in the fight against the ongoing pandemic.

“We’ve seen the outbreaks that do occur in schools or buses,” said Yellowhawk Interim Chief Executive Officer Aaron Hines. “I think this affords a level of protection for another age group.”

For Luka’s family, the day brought relief after a difficult few months.

Luka’s mother, Dara Williams Worden, was the first family member to contract the virus in August as the delta variant spread rapidly on the reservation, infecting more tribal members than any previous surge. Worden struggled in isolation for days, suffering from body aches, muscle cramps and stomach pains.

By the time Luka contracted COVID-19, the whole family was ill. Luka had been trying to distance herself from her mom. On the day she tested positive, Luka went into her mother’s room and hugged her. There was no use isolating anymore, Worden said.

“It was scary for her, seeing mom like that,” said Worden, an enrolled CTUIR member.

Worden was vaccinated, and although she fell seriously ill, she said she believes it would have been worse if she hadn’t gotten the shot. In October, her father contracted COVID-19. He was unvaccinated, Worden said.

“I wish he had been,” Worden added.

He wanted to wait and see how well the vaccines worked and what side effects there might be, Worden said. He died at the age of 67, she said.

Native Americans hit hardest by pandemic

A robust and growing body of research indicates the pandemic has disproportionately affected Native Americans. According to the most recent data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Native Americans are more likely to be hospitalized and die with COVID-19 than any other race or ethnicity in America.

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation largely has been successful at curbing the spread of infection throughout the pandemic, which health officials attribute to the tribes’ quick and strict precautions. Yellowhawk health officials have reported 681 COVID-19 cases and five deaths since the pandemic started, according to data as of Nov. 8.

But that hasn’t stopped the pandemic from touching the lives of tribal members and health care workers alike.

Summer Bryan, a Yellowhawk public health nurse and enrolled CTUIR member who organized the clinic, said “a couple” of her family members died from COVID-19. She, too, tested positive during the delta crisis and fell seriously ill. She’s vaccinated but immunocompromised. If she hadn’t gotten the shot, she likely would have been hospitalized, she said.

Bryan said her experiences have empowered her to inform family members and her community about the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines. As a nurse, she said it’s important to her to help keep the community safe and protect tribal elders. She said organizing the clinic was one way she could help bring life back to normal on the reservation.

“It makes me feel I have a responsibility,” she said, adding: “I try to be that vessel, most definitely.”

Thelma Eagleheart, whose daughter Samarah got vaccinated at the clinic, said she and her husband contracted COVID-19 in March 2020. For 17 days, she struggled to breathe and eventually got pneumonia. Back then, the tribes didn’t have COVID-19 tests. She was scared and didn’t know what to think. She watched CNN in fear as the world closed down.

More than a year-and-a-half later, Eagleheart said she still can’t sleep on her back. She said feels a heaviness she didn’t before, and when she falls ill, it’s grueling.

“Some things aren’t the same,” she said.

That’s why she was thrilled that her 8-year-old daughter decided on the morning of the clinic that she wanted to get the vaccine. She didn’t want Samarah to experience what she had.

“It’s reassuring,” she said. “I feel more secure with her going to school … I’m just so proud of her.”

One family’s choice

Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the vaccine’s emergency use among children on Oct. 29, Luka badgered her parents about when she could go get her shot.

She wanted to go back to school, away from her inconsistent Wi-Fi and lost Zoom calls. She wanted to see family she hadn’t seen in months — and the Portland Trail Blazers. She wanted to travel again and follow through on her plans to live with her friends in a California mansion.

The family followed health care workers down a hallway. Streamers with puppies on them hung from the ceiling, and balloon mats dotted the floors.

Luka sat down in front of registered nurse Adam White. She rolled up the sleeve of her Mickey Mouse T-shirt. She told White she wasn’t nervous. “She’s a pro,” Worden said.

Luka’s dad, Aaron Worden, filmed with his smartphone. As White took Luka’s arm and administered the dose, she hardly flinched. He put a Scooby Doo bandage on her arm, and she high-fived her mother.

“It’s nice to touch a shoulder and say now, you will be more likely to survive,” White said after the family had left.

Luka walked to the waiting room, where the Disney film “Moana” played from multiple large screens. She drank an apple juice box and said she felt good. Her parents said it would be a few days before they exhaled relief.

“At least we’re trying,” Worden said. “If we want to get through this, everyone has to do their part.”