Where did the snow go?

Published 9:30 am Friday, October 22, 2021

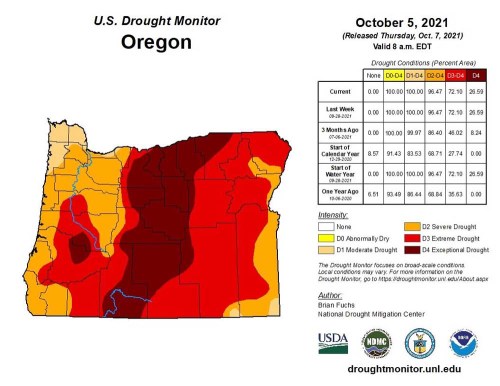

- The U.S. Drought Monitor in early October showed all of Northeastern Oregon in either exceptional drought (the worst), extreme or severe.

Jess Blatchford lives and works in the literal shadow of the Elkhorn Mountains, and when he craned his neck last winter to have a look at the peaks, more than 5,000 feet above, he liked what he saw.

Snow.

Trending

Well, of course there was snow on the heights in the coldest season.

But Blatchford also tracks the snowpack, the biggest and most vital reservoir of water to nourish crops.

And he knew that the statistics confirmed what his eyes told him about the bountiful drifts, the snow cornices that curled over the ridgecrests like frozen waves, casting shadows visible even from so far below.

On March 1, the snowpack in Northeastern Oregon was running about 29% above average. A month later the prospects for an ample supply of irrigation water were even more promising, with the snowpack about 34% above average.

But along about the middle of spring, Blatchford was still waiting, with growing impatience and no small amount of anxiety, for the promise of that wintry scene to finally reveal itself in the reality of streams threatening to burst out of their banks.

By late spring he no longer bothered to wonder about the water.

Trending

Not with Elkhorns largely bare, the formerly intact white sheen reduced to scattered splotches you had to squint to make out.

The water, Blatchford knew, just wasn’t coming.

Not in 2021.

“The snow — I think the wind just blew it all away,” Blatchford said on Sept. 21, 2021, the second day of the potato harvest at his family’s Blatchford Farms in Baker Valley.

The wind that swept across the valley on most days during the spring hastened the drought by leaching the meager moisture from the topsoil.

But Blatchford knows the bigger culprits were chilly nights that slowed the snowmelt, and the sponge-like absorption of ground still parched from the 2020 drought.

Most of that melted snow ended up in the ground rather than in streams and reservoirs.

Sumpter Valley

Dean Defrees had a similar experience during the spring at his family’s ranch in the Sumpter Valley, west of Phillips Reservoir.

Defrees said the lack of spring rain, which helps melt mountain snow and fill streams, seemed to result in much of the snowmelt soaking into the ground rather than trickling into the valleys.

“The snowpack should have been plenty,” Defrees said. “Traditionally we get some rainy periods in May and June that help bring the snow out. This year we didn’t get any.”

He said a few springs on his family’s ranch stopped flowing for the first time this summer.

Defrees said it was “depressing” to drive Highway 7 through Sumpter Valley and barely be able to make out Phillips Reservoir, which reached its minimum pool this summer.

“It’s crazy to see it that low,” Defrees said.

Although a hefty snowpack this winter will be crucial to ending the drought, Defrees said fall rain, before the ground freezes and snow falls, would also help immensely.

If autumn stays dry, Defrees fears that the situation next spring will be similar to 2021, with the dessicated soil absorbing most of the melted snow, leaving streams and reservoirs depleted for the second straight year.

North Powder Valley

Chris Heffernan saw a similar situation play out at his place several miles north of Blatchford Farms, in the North Powder Valley near the base of Ladd Canyon.

“We had a good snowpack, but it was so dry last year it went right into the ground,” said Heffernan, whose family, including his sons Sheldon and Justin, grow a variety of crops both on their own ground and on leased land in the Grande Ronde Valley.

The ponds on his family’s timbered ground near Pilcher Creek Reservoir, which usually fill and run over, this year barely reached full. And then only briefly.

“The ground soaked it all up,” Heffernan said. “There was not a lot of runoff.”

Doug Birdsall can attest to that.

Birdsall started as manager of the Powder Valley Water Control District on July 1. It was an inauspicious time to take over as the manager of an irrigation district.

Although he’s new to the job, Birdsall said he talked with longtime farmers who could remember only one other year when the two reservoirs the district owns and operates — Wolf Creek, created by the construction of Wolf Creek dam in 1974, and Pilcher Creek, created a decade later — dropped as low.

Both reservoirs, which are connected by a canal that can drain water from Pilcher Creek, which is at a higher elevation, into Wolf Creek, are west of North Powder.

“It’s very uncommon,” Birdsall said of the situation this fall.

Birdsall said Wolf Creek, the larger reservoir with a capacity of about 12,000 acre-feet, dropped to its minimum pool of 750 acre-feet at the end of summer.

(One acre-foot of water would cover one acre of flat ground to a depth of one foot.)

Pilcher Creek, which stores about 5,900 acre-feet, was nearly emptied.

Birdsall said he was able to start refilling Pilcher Creek Reservoir on Oct. 1 by diverting water from the North Fork of Anthony Creek through the Carnes Ditch.

Although the water content in the snowpack in the mountains above the two reservoirs was above average for most of the winter, farmers ended up with 70.5% of their usual water allotment, Birdsall said.

But Heffernan said he felt rather fortunate even with that amount.

“We did a lot better than a lot of regions,” Heffernan said.

But not as well as usual, in large part because spring, the season that Eastern Oregon farmers and ranchers can usually rely on to spare them from the deepest of droughts, left them in the lurch in 2021.

“We didn’t get that shot of rain like we do some years,” Heffernan said. “It was a pretty brutal year, to be honest with you.”

Statistics, in their coldly impersonal way, lend weight to Heffernan’s choice of adjectives.

For the first six months of 2021, precipitation at the Baker City Airport — rain and snow — totaled 2.44 inches. That’s 57% below average for the period.

May, which has an average rainfall of 1.42 inches at the airport, brought just 0.57 of an inch this year.

June was even worse, with just 0.21 — 83% below average.

Precipitation at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport in Pendleton amounted to 4.31 inches for the first six months of the year — 39% below average.

At the La Grande/Union County Airport, June’s rainfall total of 0.33 of an inch was 79% below average. And for the first half of 2021, precipitation there was 33% below average.

“We got beat up pretty good in the Grande Ronde Valley,” Heffernan said. “Really, it beat us all up.”

Record heat

But the weather, after depriving the region of the vital spring rains, was not finished fouling up farmers’ plans.

In the late week of June an “anomalous high pressure dome” — meteorologist-speak for the most severe heat wave on record — descended on the Northwest, driving temperatures in some places to levels they had never before reached at any time.

Temperatures topped out at 118 in Hermiston, 117 in Pendleton, 111 in John Day and 107 in La Grande.

The heatwave was slightly less severe in Baker Valley, where the maximum at the Baker City Airport was 103.

But that was still the hottest temperature ever recorded during June at the airport.

Blatchford said he’s now seen, during his career as a farmer, temperatures in June as low as 20 degrees, and as high as 103.

Both extremes have similarly detrimental effects on crops, he said.

Blatchford estimated the wheat yield on his family’s farm was about half of usual, a decline he attributes “90 percent to weather.”

“It’s one of the worst I have seen, or even heard of,” he said of 2021’s combination of excessive heat and scarcity of rain. “You just hope it’s an asterisk year.”

Burnt River country

An anomaly in an otherwise dismal year for irrigation water supplies is the Burnt River Irrigation District in southern Baker County.

The district, which uses water stored in Unity Reservoir to irrigate hay crops along the Burnt River downstream to Durkee Valley and beyond to the Huntington area, was able to supply the usual quantities of water through judicious use and cooperation among farmers, said Wes Morgan, the district’s manager.

“I’d like to take credit for it, but really I lucked out,” Morgan said.

First, Unity Reservoir filled this spring.

This itself is not unusual — the reservoir, with a relatively modest capacity of about 25,000 acre-feet, has only failed to fill a couple times since the dam was built in the late 1930s.

The other key factor, Morgan said, is the nature of the irrigation system in the district.

“The Burnt River system is a little unique in that we have a lot of flood irrigating in the hay meadows along the river bottom,” he said.

That water soaks into the soil and eventually percolates back into the river — what’s known as “return flow.”

“We like to say that by the time that water gets to Huntington we’ve worn it out,” Morgan said with a chuckle. “Return flows make a huge difference.”

But even with ample irrigation water, Morgan said he’s hearing from farmers in the district that their hay yields were down somewhat, likely a result of excessive summer heat and a cold, dry spring.

“It was tough to get things growing,” Morgan said.

Eastern Baker County

In the Eagle Valley of eastern Baker County, one of the hottest parts of the county with its elevation of about 2,200 feet — 1,200 feet lower than Baker Valley — hemp farmer Hans Hammar said the buds on this year’s plants were slower to produce flowers, and generated smaller buds, than in the three previous summers when he and his wife, Hopi Wilder, grew the industrial plant.

Hammar said he can’t say with certainty, though, whether this effect, which will reduce his yield compared with previous crops, resulted from the heatwave or from a genetic difference in the seeds he planted.

“It sure could have been the heat,” he said.

Hammar said the hemp plants, which were planted in early June and were just about a foot tall when the record heat started later in the month, seemed to endure the triple-digit temperatures with aplomb.

He thinks this might have something to do with his decision to leave his cover crop of clover on the ground, rather than killing it before planting the two acres of hemp.

That left a continuous cover of vegetation on the ground rather than expanses of brown soil that would have gotten hotter during the heatwave.

Hammar said he talked with a hemp farmer in the Ontario area who used black plastic as mulch this year — Hammer said he used paper, straw and hay — and the plastic absorbed an excessive amount of heat, harming the crop.

Hammar said he is fortunate that his property has good water rights from nearby Eagle Creek, so he had sufficient irrigation water for his efficient drip system.

“We don’t use that much water,” he said.