Bar exam proposal sparks discussion among local attorneys

Published 5:00 am Saturday, August 7, 2021

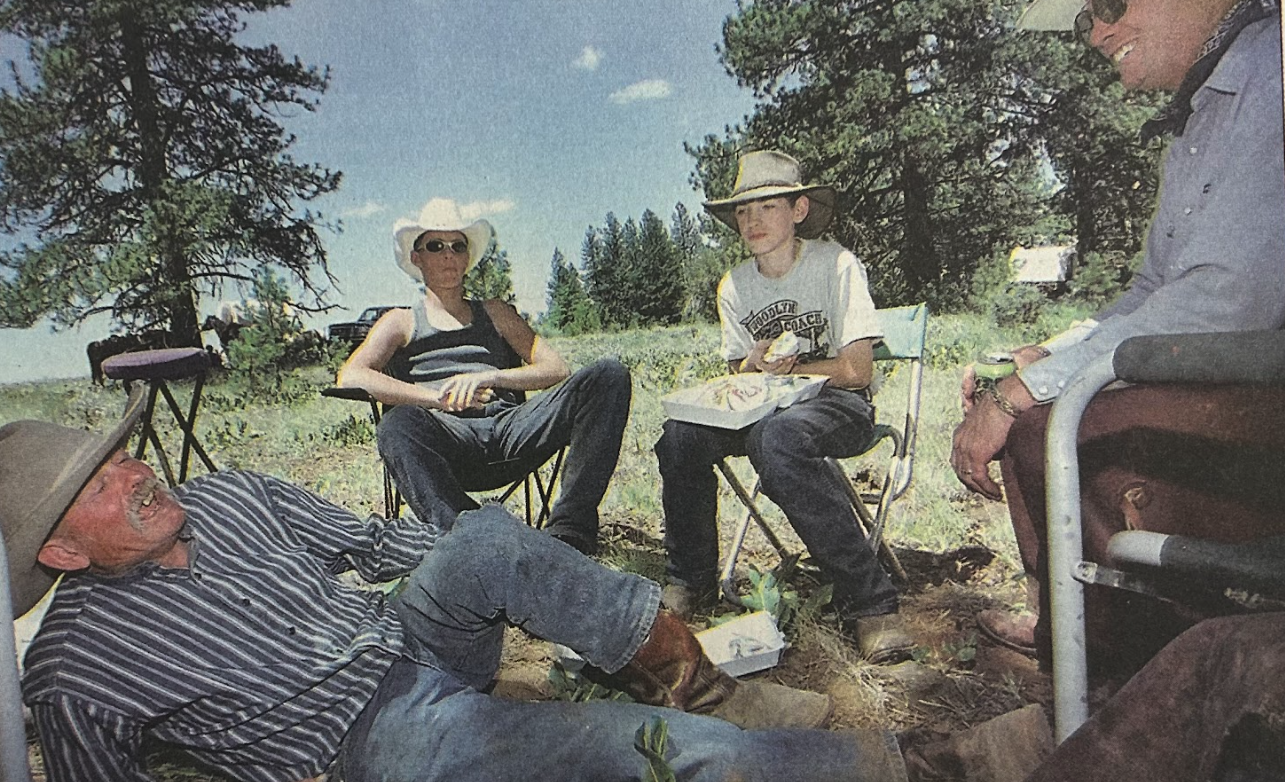

- Deputy District Attorney Zach Williams, right, speaks to Umatilla County Circuit Judge Jon Lieuallen, left, Thursday, Aug. 5, 2021, during a hearing at the Umatilla County Courthouse in Pendleton. The Oregon State Bar is considering a move to make the Unified Bar Exam optional.

PENDLETON — The Oregon State Bar is considering doing something that no other state has done before: making the Unified Bar Exam optional.

Passing the test is a requirement for practicing law in Oregon, but as the Bar and the Oregon Supreme Court begins exploring alternative paths to becoming an attorney, the topic has been heavily debated in the state’s legal community. Only a tiny fraction of Oregon Bar members practice law east of the Cascades, but like the rest of their peers, local lawyers have a wide range of opinions on the future of the bar exam.

The report

The legal class of 2020 were the first group of lawyers who were admitted to the Bar without having to take the exam.

The COVID-19 pandemic meant the state suspended the bar exam requirement to become an attorney, meaning Oregon students fresh out of law school could start practicing law without passing the test. Although the bar exam resumed in February, the Oregon Supreme Court, the body responsible for overseeing the Bar admission process, asked the Board of Bar Examiners to take it a step further and examine permanent alternatives to the test.

The result is a June 18 report from an “Alternatives to the Exam Task Force,” that made the case for two new paths to becoming a lawyer.

“The Task Force found the different pathways it explored could be crafted in a manner that ensured minimum competency standards were met,” task force Chair Joanna Perini-Abbott wrote. “Each pathway, however, had its own advantages and drawbacks in terms of equity and access issues.”

The “Oregon Experiential Pathway” would revamp Oregon law schools, requiring them to offer a more practical curriculum. Instead of focusing on legal doctrine, law schools would be required to offer courses on topics such as professional responsibility, state and local law, criminal procedure and personal income tax. Paired with an externship and a capstone project, completing enough of these courses would be sufficient in gaining admission to the Bar.

The other route, the “Supervised Practice Pathway,” would require aspiring lawyers to complete 1,000 to 1,500 hours of legal work under the supervision of an experienced attorney. During the apprenticeship, the attorney-in-training would have to do actual legal work, including representing clients, advising business or developing policies for governments or nonprofits. Once they’ve put in the hours, the Bar applicants would graduate to becoming full-fledged attorneys.

The report recommends keeping the bar exam as an option, especially since it offers some portability for attorneys looking to practice out-of-state. Lawyers also still would need to complete a law program.

Opinions from local attorneys on these new ideas varied, but few were opposed to some sort of reform

The ‘pressure test’

Intermountain Public Defenders recently looked to add another criminal defense attorney to its Pendleton-based practice. After advertising in the Oregon State Bar Bulletin, the group received zero applicants.

Justin Morton, an attorney with Intermountain Public Defenders, said recruiting lawyers to work in public defense is never easy, especially in Eastern Oregon, where practicing law tends to be less lucrative than working in the Portland area. But Morton said removing barriers to becoming a lawyer could make it easier to expand the pool of legal professionals.

Morton said if a local resident wanted to become a lawyer today, they would need to move to the Willamette Valley, the location of the state’s only three law schools, spend thousands of dollars on their education and take a test that doesn’t necessarily prepare them for a career in law.

“What prepares you to be a lawyer is being a lawyer and doing it again and again,” said Morton, who also is the president of the Sixth Judicial District Bar Association, a group that represents attorneys in Umatilla and Morrow counties.

Morton said the process has made it difficult for low-income residents and people of color from joining the profession. According to a 2017 survey from the Oregon State Bar, less than 1% of lawyers in Eastern Oregon, an area that includes Central Oregon and the Columbia River Gorge, identify as Hispanic or Latino, although the data comes with the caveat that all the racial data is reported.

Pendleton attorney Blaine Clooten has been a vocal opponent of the proposed alternatives to the exam, going as far as to write Oregon Supreme Court Chief Justice Martha Walters.

In an interview, Clooten wrote that the Bar exam provided a critical “stress test” for prospective lawyers, and giving law students a chance to bypass the exam could hurt clients and damage the profession’s reputation.

“Just because you have more attorneys doesn’t mean you have more competent attorneys,” he said.

However, Clooten does think there’s room for reform, especially the exorbitant cost of law school, which makes the process “classist” by shutting out impoverished students.

Despite all the debate, the Oregon State Bar hasn’t turned the proposals into policy just yet. The Bar and the Supreme Court will continue to accept public comment on the proposals through Aug. 23. Comments can be made at the Bar website at https://bit.ly/3itcuzw.