‘Just miserable’: Farmers, ranchers confront historic drought

Published 7:29 am Friday, July 2, 2021

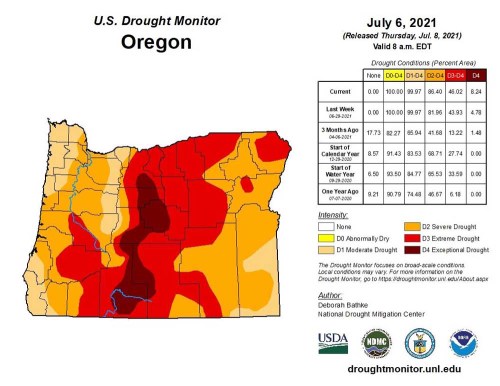

- Drought monitor (NEW)

BAKER CITY — Mark Bennett had rarely if ever been happier to welcome a soggy spring storm.

He tracked its progress as the sodden clouds swept inland from the Pacific Ocean and began their moist march across Oregon, seemingly headed more or less directly for the cattle ranch in southern Baker County that Bennett and his wife, Patti, own and operate.

Trending

But just as this drought-interrupting tempest was poised to deliver its dust-laying showers on June 10, the storm veered.

This capricious shift, so late and so cruel, left the Bennetts’ ranch — and indeed the whole of Baker County and much of Northeastern Oregon — almost completely dry.

Yet places both to the south and to the east were doused.

Boise, which frequently receives the scant remnants of storms that bring significant rain to the higher terrain of Baker County, had a record-setting 0.71 of an inch that day.

Bennett later talked with friends who have a ranch near Harper, in northern Malheur County maybe 30 air miles from his place.

“They had flooding, and we didn’t get a drop,” Bennett said in an interview on June 28, his chagrin still obvious in his voice almost three weeks later.

Trending

“We didn’t get a drop here.”

What the Bennetts’ ranch did get that June day is what they, and farmers and ranchers across much of the rest of Northeastern Oregon, have gotten their fill of this year: wind.

The scarcity of rain during 2021 has been troubling enough.

But the nearly incessant gusts that have buffeted the region, whipping desiccated topsoil into dust clouds, have exacerbated an already dire situation.

“Everything’s just unbelievably dry,” Bennett said. “And we’ve had terrible wind every time we’ve had any moisture.”

For the first six months of 2021, precipitation at the Baker City Airport — rain and snow — totaled 2.44 inches. That’s 57% below average for the period.

Neither May, which is the wettest month on average at the airport, nor June, which ranks second, brought the relief that they often do even in years when the winter and early spring are drier than usual.

May, which has an average rainfall of 1.42 inches at the airport, brought just 0.57 of an inch this year.

June was even worse, with just 0.21 — 83% below average.

The situation is only slightly better in Umatilla and Union counties.

Precipitation at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport in Pendleton amounted to 4.31 inches for the first six months of the year — 39% below average.

That’s despite a series of snowstorms during February that pushed the monthly total to 2.11 inches, nearly double average.

At the La Grande/Union County Airport, that June 10 storm that Bennett was anticipating bestowed the bare statistical minimum amount of moisture to qualify as measurable rain — 0.01 of an inch.

June’s total of 0.33 of an inch was 79% below average. And for the first half of 2021, precipitation was 33% below average.

Union County is faring better than the rest of the region on the drought monitor, however.

Unlike Baker, Wallowa, Grant, Umatilla and Morrow counties, all of which have large areas in extreme drought at the end of June, all but a tiny slice in the southern part of Union County is rated as severe drought, one step below extreme on the severity scale.

All six of those counties, though — including Union — have been declared drought disaster areas by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, on the request of elected commissioners in each county.

Back in Baker County, Bennett’s interest in the severity of the drought is twofold.

In addition to owning a cattle ranch near Unity for more than 40 years, Bennett is one the three Baker County commissioners.

He and fellow commissioners Bill Harvey and Bruce Nichols on April 7 approved a resolution declaring a drought emergency in the county.

Brown followed suit by declaring a drought in Baker County on May 10, the same day as the governor did so for Morrow County.

(Brown made drought declarations for the four other counties during June.)

Conditions have only worsened since early May, Bennett said.

He and his wife have had to haul drinking water to some of their cattle for the first time ever.

Those cattle graze on pastures near two springs that have been reliable — until 2021.

Bennett said the springs didn’t go dry.

“They just never ran at all,” he said.

Although snowpack in the mountains was near average this winter, Bennett said it’s clear that most of the melting snow this spring soaked into the soil, which was drier than usual due to the drought that started in the summer of 2020.

“I’ve had to dig a couple of holes with a backhoe this spring, and it’s just dust,” Bennett said.

With springs failing to flow, Bennett has had to buy a trailer and tank to haul water about 2 1/2 miles to the pasture where his cattle are grazing.

Although this year’s grass crop is about half of average, there is at least enough forage to keep his cattle fed.

“It varies widely from field to field,” Bennett said. “The areas protected from the wind are a lot better.”

Later this summer he’ll move herds to higher-elevation pastures that do have water.

But unless the weather patterns shift dramatically and bring a lot of rain this summer — hardly something to count on in a region that lies within the rain shadow cast by the Cascade Mountains — Bennett fears this fall will be even more difficult for many ranchers.

Irrigation water will be short — especially for ranchers, including the Bennetts, who don’t have access to water stored in a reservoir.

The lack of water means pastures where cattle normally graze during the fall will either be short on grass or, worse still, not usable at all.

That means ranchers will need to buy more hay, and earlier, but Bennett said the drought will also cut hay yields.

The basic equation is simple, and frightening, he said — more demand for hay, but less hay available.

“Our fall season’s going to really hurt,” Bennett said.

Ralph Morgan shares Bennett’s concern about what’s to come for the rest of 2021.

Morgan, who has a ranch along the Powder River between Baker City and Sumpter, said the current drought seems to him without precedent.

“We’ve had droughts, but it seems to me like this is the worst it’s ever been,” Morgan said in an interview on June 29. “The heat coming this early, and we’ve had the wind every day.”

Morgan was talking during a record-breaking heat wave that descended on the Pacific Northwest the final week of June.

The temperature reached 112 at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport on June 27, 113 degrees on June 28, and an all-time record of 117 on June 29.

But Morgan said it wasn’t only heat, but also chilly temperatures earlier in the spring, that contributed to the parched conditions.

Cool nights in particular prevented the snowpack from melting rapidly, and Morgan, like Bennett, said it seemed that much of the melted snow seeped into the ground rather than trickling into the streams that farmers and ranchers use to irrigate their fields and pastures.

Morgan said fields in Bowen Valley, just south of Baker City, were damp for two or three days after lower-elevation snow melted, but after that there was little runoff.

The combination of spring chill and nearly constant wind also stunted the growth of early grass that is vital forage for cattle, Morgan said.

He said he was repairing fence near Bald Mountain, along the divide between the Powder and Burnt rivers, in late June and grass that normally grows several inches high was barely an inch tall and already going to seed.

“With no moisture there’s no chance for it to grow,” Morgan said. “It’s looking pretty dire.”

The situation is slightly more promising in parts of southern Baker County, where farmers and ranchers have access to water stored in Unity Reservoir, along the Burnt River.

The reservoir, which is smaller than most others in the region, filled this spring, as it usually does.

That was despite a snowpack that was a bit above average but produced relatively little runoff, said Wes Morgan, who manages the Burnt River Irrigation District.

“We lucked out,” he said.

Morgan said farmers and ranchers along the Burnt River below Unity Reservoir have been cooperating to make the most of the available water.

“We’ll make it through the irrigation season with no water to spare,” he said.

Morgan expects the hay crop on ground irrigated with water from the reservoir will be near or slightly below average.

At the end of June, Unity Reservoir was holding a little more than 17,000 acre-feet of water — about 68% of its capacity.

Bill Moore, who has a ranch near Unity and is a former president of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association, had a simple description for conditions as July began.

“Just miserable,” Moore said. “There’s no other way of putting it.”

Moore said water for cattle is scarce, and grass at lower elevations is short and already curing.

“It looks like what it should be in mid to late August,” Moore said. “We’re used to drying out in August, but not in June.”

Farmers and ranchers who live above Unity Reservoir, and thus have to depend on streams for irrigation water, will soon see those sources dwindle, he said.

Creeks continued to flow at decent volumes into mid June, but then the heat wave hit.

“With this heat it’s fading pretty fast,” Moore said of stream levels.

On the positive side of the ledger, Moore said water from Unity Reservoir should ensure that producers downstream from the reservoir can have good crops of alfalfa and wild hay.

And grass at higher elevations, where cattle graze for much of the summer, is relatively lush and tall, a remnant of a winter snowpack that was around average.

Reservoir recedes

Compared with what’s happening at another reservoir, about 15 miles north of Unity, Morgan’s use of the adjective “lucky” seems appropriate.

Phillips Reservoir, on the Powder River about 17 miles southwest of Baker City, hasn’t been so puny at the start of summer since it first began to fill in the spring of 1968.

On the last day of June the reservoir was holding about 10,000 acre-feet of water — about 14% of its capacity.

(One acre-foot of water would cover one acre of flat ground to a depth of one foot. It’s equal to about 325,000 gallons.)

Phillips Reservoir’s previous low water mark for June 30 was in 1992, when it was holding almost twice as much water — 19,500 acre-feet.

Mason Dam, which created the reservoir, was built to store water to irrigate more than 30,000 acres, mainly in the Baker Valley.

Mark Ward’s family is among those who have rights to stored water in the reservoir. The Wards grow potatoes, wheat, peppermint and silage corn.

Mark Ward said the 1977 drought, one of the worst in Oregon during the 20th century, has long been a measuring stick for dry years.

But Ward said 2021 is forcing people to readjust their perspective.

“I don’t remember one this bad,” he said.

In 1977, for perspective, Phillips Reservoir at the end of June held 33,500 acre-foot of water — more than three times more than it impounded on that day this year.

The problem in 1977 was that the mountain snowpack — then as now the biggest source of water by a wide margin — was skimpy.

But the 2020-21 snowpack, as mentioned, was close to average in most areas — and above average in some.

That snow just never made it into the streams, most notably the Powder River itself, that feed Phillips Reservoir, Ward said.

Like Ralph Morgan, Ward blames the chilly nights for slowing the snowmelt, allowing the water to soak into the ground.

Ward also cites the wind as a factor.

He believes the same gusts that leached moisture from his Baker Valley fields did the same with the snowpack in the Elkhorn Mountains that rise more than 5,000 feet above the valley.

During most springs there’s at least one storm that brings both rain and temperatures warm enough to ensure the precipitation falls as liquid even on the highest peaks, Ward said. These “rain on snow” events cause a rapid snowmelt that causes a flush of water in streams and puts a lot of water into Phillips and other reservoirs.

There was no such event in 2021.

Not in 2020, either.

Data from a river gaging station on the Powder River just above Phillips Reservoir illustrates Ward’s point.

During the spring of 2021, the daily average flow at that station peaked at 182 cubic feet per second (cfs) on May 18. The daily average exceeded 100 cfs on just two days during April.

The situation was similar in 2020.

But in 2019, which was a much more typical spring, the daily average flow at the gaging station surpassed 100 cfs every day in April, including a peak of 436 cfs on April 9 — more than double the peak during 2021 or 2020.

During the spring of 2019 the river flow was higher than the 2021 maximum of 182 cfs on 56 days, including 34 consecutive days during May and early June.

The river was flowing as high as 195 cfs as late as June 8, 2019.

In 2021, by contrast, the flow, which never reached that level, had plummeted to 88 cfs by June 8, and to a comparative trickle — 6.2 cfs — by June 28.

Heat wave prompts concern about lower crop yields

The rapid drop in the river level in late June coincided with the most severe June heat wave on record in the region, with temperatures reaching 117 degrees at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport on June 29.

Temperatures weren’t as torrid in Baker Valley — peaking at 102 on June 29, tying the all-time record high for the month — but Ward said consecutive days in the low 100s can reduce both yields and the quality of his family’s potato crop.

On the afternoon of June 29, Ward gave a phone interview while he was sitting in the cab of his pickup truck parked beside one of his fields.

“I have the A/C on full blast and I’m still uncomfortable,” Ward said. “The thermometer shows 105. Potatoes do not like 105-degree weather. They shut down.”

Warm nights aren’t conducive to a bumper spud crop, either — Ward said potatoes fare best when temperature dip to at least 55 at night.

But that very morning, he said, the temperature at his house didn’t go below 68.

“We still have a chance for a good yield, but this has taken the top end yield potential off the table,” Ward said.

He called the heat wave, combined with the increasingly severe drought, a “double gut-punch” to farmers and ranchers in the region.