Oregon drier than last year as fire season begins

Published 12:00 pm Wednesday, June 23, 2021

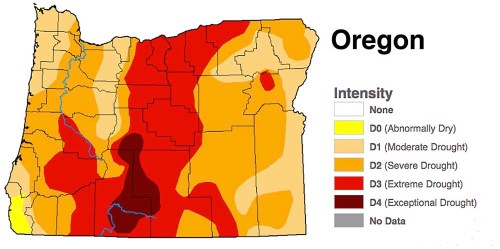

- Oregon Drought monitor June 22

CORVALLIS — Historically dry conditions are raising concerns that another long wildfire season may be ahead in Oregon.

Experts at Oregon State University held a virtual forum Monday, June 21, to discuss this year’s drought and fire conditions. Meanwhile, several large blazes are already burning thousands of acres and temperatures are expected to reach into the triple digits statewide.

“Right now, we are drier at this point than we were at this point last year,” said Larry O’Neill, state climatologist with the Oregon Climate Service. “I think we’re in the thick of it right now, at least in terms of the drought conditions and how it projects onto wildfire risk.”

As of June 21, the S-503 Fire was the largest, burning 6,201 acres near the Warm Springs Reservation in Central Oregon. The fire started June 18, and was 10% contained. A cause has not been determined.

In Southern Oregon, the Cutoff Fire started June 19 and has burned 1,150 acres on state forestland about 6 miles north of Bonanza. It is 12% contained, and the cause remains under investigation.

Earlier this month, a pair of lightning-sparked fires in Northeast Oregon — the Joseph Canyon and Dry Creek fires — torched 9,195 acres of timber and rangeland. Those two fires were mostly contained on June 11.

Meg Krawchuk, an associate professor at the College of Forestry, said conditions on the ground are more characteristic of what firefighters might expect in July, rather than June.

“When we have early and longstanding drought, we’re more likely to have fires burning,” Krawchuk said.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, all of Oregon is listed in some stage of drought, including 77% in “severe” drought, 36% in “extreme” drought and a little under 5% in the worst category of “exceptional” drought.

The driest conditions are spread over Central and Eastern Oregon, according to O’Neill, the state climatologist. Klamath, Deschutes, Crook, Jefferson and Wasco counties all experienced their driest or second-driest spring on record, he said.

In addition, the USDA reports that 80% of the state’s cropland and livestock pastures are rated as either “short” or “very short” of soil moisture.

“That’s also very concerning right now for a lot of the agricultural and livestock producers here,” O’Neill said. “Things are looking a little bit bleak.”

Oregon is already coming off of a record fire season in 2020 during which more than 1 million acres burned, particularly in Western Oregon, where a series of post-Labor Day conflagrations fanned by strong easterly winds consumed entire towns.

Lisa Ellsworth, an assistant professor who studies fire behavior and rangeland ecology at the College of Agricultural Sciences, said Oregon is not at the point yet where fire season lasts year-round, as in California. But the trend toward higher temperatures and more severe drought across the West is having an impact.

“Twenty years ago, when I fought wildland fire, our seasons looked nothing like this,” she said.

Erica Fleishman, director of the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute, said it is impossible to pin the trend entirely on climate change, but “the types of weather patterns we’re seeing this year are consistent with what has been observed and what is projected as climate continues to change.”

“Climate change is a factor,” Fleishman said. “We cannot simply pin it all on climate change, but it is a factor.”

Hotter and drier weather does not always necessarily mean more fires. There must be a spark, in combination with the right conditions, for wildfire to spread.

Ellsworth said more than 80% of fires in the West are caused by humans, underscoring the need for people to be careful working and recreating outdoors.

“While we can’t do a whole lot about the drought conditions we are facing right now, we can do a whole lot about the ignition sources … managing people and managing that potential for wildfire as people are out there recreating,” she said.