Farmers, ranchers fear drought after parched March

Published 2:19 pm Thursday, April 1, 2021

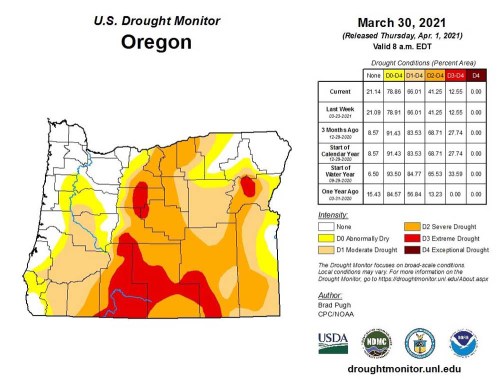

- Drought conditions in Oregon as of March 30, 2021.

Mud is a symbol of spring in Northeast Oregon nearly as reliable as the bright yellow buttercup and the soft green of a wheat field.

But Wes Morgan isn’t seeing much mud this spring.

Plenty of snow, in places.

And in others, clouds of dust roiling behind his rig when he drives an unpaved road.

But the mucky sludge that clogs truck tires and spatters windshields during the transition from winter to summer has been conspicuous in 2021 by its absence, said Morgan, who manages the Burnt River Irrigation District in southern Baker County.

The contrast between the mountains, where the snow still lay deep the first week of April, and the already arid lowlands, was much more distinct than usual for the season, Morgan said.

“It’s a strange spring we’ve had,” he said on April 5.

The situation is promising in one respect.

With the snowpack above average in most parts of the region as April began, irrigation water supplies from some reservoirs should be good this summer, Morgan said.

The reservoir he manages — Unity — was at 82% of capacity in early April, and Morgan was preparing to release more water from the reservoir to make room for the melting snow that will flow in over the next couple months.

The snowpack is especially prodigious in the northern Blue Mountains, where the water content in the snow at High Ridge, near Tollgate, was 70% above average the first week of April.

But those dust clouds have Morgan worried.

He worries about the owners of rangelands and pastures that don’t have access to water stored in reservoirs such as Unity.

He worries about drought.

The continuation of drought, to be specific.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor Index, as of the first week of April a drought that started last summer persists in much of Baker County, with conditions ranging from moderate to severe in much of the central part of the county, with a roughly oval-shaped zone of extreme drought in part of the county that includes Baker Valley.

The situation prompted the Baker County Board of Commissioners on April 7 to declare a drought disaster in the county and to ask Gov. Kate Brown as well as U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack to follow suit.

State and federal drought declarations could make county farmers and ranchers eligible for financial aid, and give state water regulators more flexibility in allocating water this summer.

Elsewhere in the region, the southern part of Union County was in either moderate drought or rated as abnormally dry, while the northern part of the county, along with all of Wallowa County and the eastern part of Umatilla County, are rated as normal.

A compressed winterMark Bennett, a Baker County commissioner who also owns a cattle ranch in the southern part of the county, like Morgan has watched, with similar trepidation, as clouds of dust billowed behind his pickup truck early this spring.

Bennett attributes this arid predicament to a couple of factors.

First, and most obviously, is the 2020 drought. Like another scourge — the COVID-19 pandemic — the drought has lingered into 2021 in Baker County.

But Bennett said the rapid shift from damp, wintry conditions to dusty soil more typical of August than of April also reflects the nature of the past winter.

Most notably, that much of the winter’s chilly power was packed into the middle of February.

The largest share of the season’s snow in the valleys — especially in the Columbia Basin — fell from Feb. 9-18, when an onslaught of arctic air pushed south from Canada.

March was tranquil by contrast.

Also much drier than average.

The Eastern Oregon Regional Airport in Pendleton, for instance, recorded just 0.32 of an inch of precipitation during the month, one inch below average.

The Baker City Airport’s March total was a paltry 0.14 of an inch, less than one-quarter of average.

The La Grande Airport was damp by comparison, but even its March total of 1.15 inches was almost a third of an inch below average.

Bennett said that once the valley snow had melted after the arctic outbreak in February, winter was all but over.

“Once the frost went out of the ground, it just became dry,” he said.

Morgan’s rising reservoir is no consolation for Bennett, either — the ranch he and his wife, Patti, own is outside the irrigation district and doesn’t get any water from Unity Reservoir.

“Those of us who depend on non-storage water, it’ll be a tough year,” Bennett said.

But he quickly amends that unequivocal prediction.

The potential savior, as always for farmers and ranchers who toil in the considerable rain shadow cast by the Cascade Mountains, is spring rain.

And often as not the seasonal downpours arrive to provide at least some relief.

May, on average, is the wettest month in Baker County.

And June ranks a close second.

“If it starts raining, that obviously changes the dynamics,” Bennett said.

Mark Ward certainly wouldn’t begrudge a few cloudbursts.

Not even if a tempest turned his family’s fields in Baker Valley into temporarily muddy messes.

“If a rainstorm keeps me out of the fields, I’m OK with that,” Ward said.

The Wards grow potatoes, wheat, peppermint, alfalfa and silage corn, among other crops.

Mark Ward said that despite the relatively brief bout of wintry weather in February, and the stingy skies that prevailed during March, the soil moisture in his family’s fields was “pretty good” the last week of March.

“It’s not mud but it’s not dust,” Ward said.

He’s much less pleased with another weather phenomenon.

Wind.

A series of storms that swept through the region starting in early March delivered sparse precipitation, and in some places scarcely a drop or a flake.

But the parade of cold fronts produced copious amounts of wind.

This isn’t uncommon, to be sure.

Wind, in the most basic meteorological sense, is merely the movement of air from areas of high pressure to low. When a cold front, which is the dividing line both between warm and cold air and between higher and lower pressure, pushes off to the southeast, the air pressure in Northeast Oregon rises.

The resulting pressure gradient causes air to rush toward the departing cold front, which explains the prevailing wind directions of west, northwest and north, depending on the terrain.

The canyons and valleys, notably the Grande Ronde, North Powder and Baker valleys, and Ladd and Pyles canyons, act as natural funnels, squeezing the air and causing the wind to accelerate.

Wind gusts topped 30 mph on 12 days in March at both the Baker City Airport and the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport, with peak gusts topping 50 mph on several days in both places.

“A 50 mph wind, that sucks a lot of moisture out of the ground,” Ward said.

Umatilla County outlook

Oregonians typically divide the state geographically between east and west. But for the 2021 irrigation season, Scott Oviatt is splitting Oregon between north and south.

The snow survey supervisor for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Oregon office, Oviatt said people could draw a line between Ontario and Eugene. South of the line will be dealing with drought conditions this summer. North of the line got some much needed precipitation that helped build the snow pack.

That bodes well for the Umatilla, Walla Walla and Willow subbasins, the main areas where Umatilla County farmers draw their water to grow crops like wheat, potatoes, onions and watermelons.

Oviatt said the snowpacks in Umatilla County are above average this year, aided by the late season snow storm in February. But irrigators and other observers must remain vigilant because a warm rain event or an extended period of unseasonably warm weather could change the outlook.

Eastern Oregon’s increasingly erratic weather patterns and the region’s finite supply of groundwater inspired the formation of the Northeast Oregon Water Association and its mission to help irrigators access water from the Columbia River.

J.R. Cook, NOWA’s executive director, said 2021 will be the first full-year the organization has had two of its irrigation projects in operation. As a result, Cook said the farmers that participate in the projects will have access to a new source of water that is equivalent to the amount of water stored in the McKay Reservoir.

Despite the advances NOWA has made, Cook said there’s still more work to do to keep agriculture sustainable in the region.

“It’s a shot in the arm but it’s not a silver bullet,” he said.

Among the projects NOWA is still working on is building new water storage that will collect water during the high-running years to insulate farmers from the lean ones.

Abundant February precipitation improved water outlook in John Day Basin

Grant County streamflow forecasts improved significantly from February to March but declined somewhat by April 1 due to the dry March, according to the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Water Supply Outlook Report released April 1.

Strawberry Creek near Prairie City is expected to be at 85% of average streamflow from April through September. The Middle Fork John Day River at Ritter and the North Fork John Day River at Monument are forecast at 98% of average.

Also in the basin, Camas Creek near Ukiah is expected to be at 138%, while Mountain Creek near Mitchell is expected to be at 65%.

Precipitation was 178% of average in the John Day Basin in February but just 44% of average in March, bringing precipitation for the water year, which starts Oct. 1, to 90% of average as of April 1.

Except for November, with close to 120% of average, precipitation during the other months this water year have been well below average with October and December below 60% and January just over 80%.

Snowpack in the John Day Basin was 121% of normal April 1, a small drop from 127% at the start of March but remaining above the 92% at the start of February.