Potato growers face challenges

Published 9:08 am Tuesday, March 30, 2021

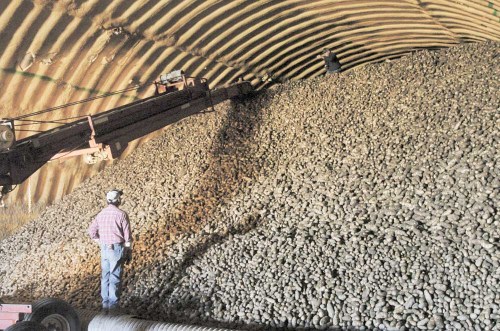

- Eric Olson, left, checks the spud storage operation at Ward Farms near Baker City being handled by Bob Adams, top of pile, who controls the conveyor inside the cellar.

A year ago, Mark Ward was worried about the potato crop he was preparing to plant in the Baker Valley fields his family has farmed for many decades.

Today he’s somewhat more confident.

Trending

And not a little relieved that the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t precipitate the economic disaster that seemed plausible, even probable, in March and April of 2020.

Still and all, Ward doesn’t expect the ups and downs to level out.

“Roller coaster ride is how I would describe the last 12 months,” Ward said in late March 2021.

The stomach-churning drop started just about a year ago.

With the nation — indeed, the world — reeling from the unexpected arrival of the new virus, restaurants either closed or offered takeout meals only.

Sporting events were canceled.

Trending

People stopped traveling, which meant the drive-thru lanes of fast-food restaurants, at least for a while, weren’t nearly as congested as usual.

With nobody watching games from the bleachers, and few if any people sitting at tables and booths in restaurants, the demand for French fries and other processed potato products plummeted.

“In March and April there was a big dip,” said Ward, who is the chairman of the Oregon Potato Commission.

The uncertain and unprecedented situation provoked anxiety among potato farmers, he said. They wondered not only whether there would be a market for the potatoes they had just planted or were preparing to plant — the Ward family sows its fields at the start of May — but they worried too about potatoes in storage.

“When restaurants closed, processors made some drastic cuts,” Ward said.

In some places, although not in Baker Valley, farmers had to plow under potatoes they had planted because potato processors severely cut production, Ward said.

Just a few growers in the Columbia Basin had to take that unusual step and sow a different crop in place of the recently planted potatoes, said Dale Lathim, executive director of Potato Growers of Washington.

Because the growing season is much longer in the Columbia Basin than in Baker Valley — the latter being more than 2,000 feet higher in elevation — potato farmers in the Basin plant their crop in late February or early March, Lathim said.

That meant they had seed potatoes in the ground when the pandemic started and processors slashed their production volume by about 20%, he said.

Some affected growers chose to raise the 2020 potato crop without a contract and hope they could sell the spuds on the open market, Lathim said.

A few plowed under the potatoes and planted other crops.

Fortunately, Lathim said, the farmers who chose the latter, unpalatable option, although they didn’t make nearly as much as they would have from potatoes, did make a small profit from their hastily planted crops rather than taking a potential loss of hundreds of dollars per acre.

Retail market, fast-food restaurants recover rapidly

The precipitous drop in demand for frozen potatoes prompted by the pandemic was relatively brief.

Ward said the market “recovered nicely” by June 2020, driven in part by demand for potatoes, both fresh spuds and frozen processed products such as fries, at grocery stores.

“People were eating at home, relearning to cook at home,” he said. “That was definitely a bright spot. There was a tremendous increase in sales at grocery stores.”

Ward said he was gratified at how rapidly the industry adjusted from supplying potatoes to the restaurant and food service industry, which buy in larger quantities, to the different demands of the retail sector.

“Kudos to everyone in the industry,” Ward said. “They got products onto the shelves at the retail level.”

The “panic-buying” that was a symbol of the early days of the pandemic — although toilet paper, not potatoes, was the most infamous of the hoarded products — helped too, Ward said.

“I talked to people who, for about two weeks, couldn’t find a potato in the grocery store,” he said.

Lathim said he wasn’t surprised that grocery sales of potatoes skyrocketed after restaurants closed or were severely limited.

“With the restaurant option taken off the table, so to speak, French fries and other convenience foods flew off the shelf,” he said. “All grocery items took a big jump last spring, and that was to be expected.”

Lathim said he didn’t anticipate, however, how rapidly sales from fast-food restaurants rebounded.

With drive-thrus the main option, sales for some franchises exceeded even pre-pandemic levels, he said.

One reason, Lathim said, is that customers were more likely to buy a meal not just for themselves, but for the entire family.

The “steady rise” in fast-food sales after the first month or so of the pandemic was crucial for the frozen potato business, Lathim said, because those franchises make up about 70% of the demand for those products, particularly French fries.

Potato prospects for 2021

Although the pandemic continues, the potato market has stabilized, at least compared with conditions a year ago, Ward said.

He said the supply of potatoes in storage is slightly above average, which has contributed to a 10% cut in acres planted in potatoes in Baker Valley this year. Growers in the valley contract with the Oregon Potato Co. and J.R. Simplot Co., Ward said.

Lathim said Columbia Basin potato growers contracting with two processors will have acreages slightly above 2020 levels but below the 2019 figure. Growers working with a third processor will have an increase in acreage to meet the demand of a new processing plant slated to open in December 2021, he said.

The bigger problems with the 2021 outlook are prices, which are dropping, and production costs, which are rising.

Lathim said processors in the Columbia Basin, which include Lamb Weston, J.R. Simplot and McCain Foods, in effect set the potato market for the rest of the nation because that region not only plants its spud crop earlier, but it also has large volumes.

Lathim said processors are proposing a price cut for the 2021 crop of about 3%.

Ward expects that will be the figure adopted across the region.

If the 3% price cut prevails, as Ward expects, it will not be the only challenge for potato growers.

He said production costs, including fuel, fertilizer and equipment, are projected to increase.

Lathim pegs the increase at a bit more than 4%.

“That seven percent swing is a hit growers have not experienced before,” he said. “Most of the growers are in a position where they can survive this kind of hit for a year, maybe two. But it’s certainly not a sustainable level.”

The combination of lower prices and higher farming costs means farmers, even more than usual, will need to manage their crops to ensure the quality and yields are as high as possible, Lathim said.

“Everybody’s going to be hyper-vigilant to maximize both yields and quality,” he said.

That means, for instance, that growers have planted potatoes only on the higher-quality ground, rather than taking a risk on sowing less-productive fields, Lathim said.

Ward said the turmoil in the potato market, and in the economy overall, has slowed the normal process of planning for the 2021 crop.

In the last week of March he said it was possible that his family will plant its 2021 potatoes with a commitment from buyers for volume, but without a signed contract for a specific number of acres.

If that proves out, it will be just the third time that has happened for the Wards in more than 30 years, he said.

Changes in Washington, D.C.

But even with contracts in place, uncertainties will remain.

Ward said the change from the Trump to the Biden administration raises questions, most notably with international trade agreements.

“Trade is vital to Oregon potatoes,” he said. “Sixty-five percent of the state’s potatoes are exported.”

Ward said he will be closely following the new administration’s approach to trade with China, a massive market that Oregon potato growers have not been able to access.

There’s also an unsettled lawsuit with Mexico regarding the ability of American farmers to sell fresh potatoes in that country.

The international market news is not wholly negative, though.

“Japan is a bright spot,” Ward said. “That’s our number one trading partner. Our exports are doing quite well there.”