A slice of life: A lesson from a Kalahari Bushman girl

Published 6:00 am Saturday, January 23, 2021

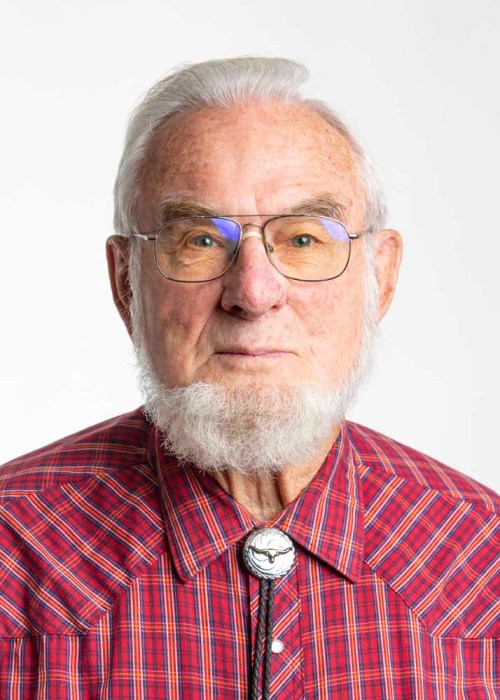

- Clark

Have you seen the movie “The Gods Must Be Crazy”? If not, please do.

It is a wonderful film involving the various tribes of people who inhabit Southern Africa and how they relate to each other. It is funny, touching — and even a good romance too.

The central character is a man of the San tribe, a group we know as Kalahari Bushmen. The standard image of the San is deep bush people in the Kalahari desert of Botswana who live a basic lifestyle — men with little loin cloths, bare-breasted women, children with minimal clothing, and a diet of dug-up roots, bushmeat, and water from dewdrops. The San are an isolated people in the Kalahari and have clearly defined features that are unique to their tribe, so a San is very easy to distinguish from other people.

I was on a job in Botswana dealing with livestock disease problems and had a weekend clear. The manager of the bed-and-breakfast where I was staying had a brother, a county counselor (a position similar to our congressional representative) — who offered to take me out sight-seeing to a rhinoceros reserve.

The lunch entertainment at the little restaurant turned out to be a black rhino (the species known to be more dangerous) who came sauntering across the lawn and went to the swimming pool for a drink. He then took a nap in the shade, another drink, a quick snack on a bush and departed. Very curious behavior for a rhino and this was interesting, but I’d seen lots of rhinos in East Africa. But then something happened that was a significant lesson for me.

Our waitress at lunch was a young San woman — that distinctive face was unmistakable — and my stereotype immediately came to mind, but she was wearing a waitress uniform. After lunch my host opened his computer to show me something and it balked — he could not make it work. As our San waitress cleared our table she saw his struggle with the computer and asked if she could help. My stereotype of San leapt into operation. What? A San girl fixing a computer?

Frustrated, he handed the computer to her. Really?

Click, click, click, click, click.

And then “There you are,” as she handed the computer back to him with a smile — fixed and working perfectly.

The lesson for me was about the immediate stereotype into which I had cast that young woman because of her obvious tribal identity. It was ignorant and arrogant of me. History has moved along and the San people no longer fit the movie stereotype. Why couldn’t a modern San have computer savvy? Why did I allow myself to have that unconscious bias? Was I demonstrating my own tribalism?

I had been working in Africa for about 15 years, and when I first went to Tanzania in 1964 the ratio of Black people to white people was about 40,000-to-1, so I was entirely accustomed to being in a minority. When I thought about this situation, I was ashamed to admit that after years of experience working with Eastern Africans but not Southern Africans, I had this peculiar response based on a stereotype from a movie as to what Southern African San would be.

I should know better than that.

Currently, a major issue here in America is systemic racism. Indeed, it is truly here — and a component of that systemic racism is personal racism. A component of personal racism is stereotypes, and those stereotypes cripple us in how we relate with the people who are trapped in our self-imposed bias. If we accept stereotypes developed from movies or not-necessarily-true stories or violent television programs, we do a disservice to both ourselves and to the stereotyped persons we meet. In that process we both are wounded, and I myself had been caught in that trap.

Can this be solved and the wounds healed? Yes.

We can do it, but it takes effort and thought and making alterations to our perceptions and stereotypes and behaviors. We’ll all be better off when we do so, all across the nation.