Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center honors past

Published 7:00 am Friday, October 9, 2020

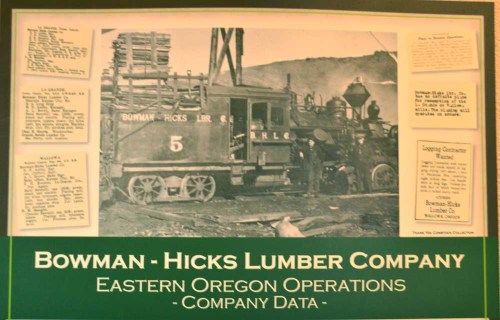

- A display shows timber production data for the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Co. that operated the former logging town of Maxville, which existed north of Wallowa from 1923 to 1933. The photo in the display at the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center in Joseph is of one of the locomotives used to move logs.

JOSEPH — One of the centerpieces of Wallowa County’s long history in the timber industry is the former logging town of Maxville. It’s also a prime example of the ethnic diversity that has long existed here.

Since 2008, Gwen Trice, the daughter of one of the original Maxville loggers, has been operating the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center to keep alive the history associated with this vital part of Wallowa County’s past. The center first was located in Enterprise, then moved to Wallowa — about 15 miles south of the old Maxville townsite along Promise Road — and now is located at 103 N. Main St. in Joseph.

Trending

“That’s just how it worked for us. It was a stronger business model to be in a space where we get up to 1,500 people in a summer,” Trice said.

Closed as nonessential at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March, the center hasn’t disappeared with the pandemic. Trice said it remains open by appointment in a “soft reopening” and is planning its fundraising gala from 5:30-8 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 24.

“We can’t have a line of people outside waiting to come in,” she said of the soft reopening. “We need to make sure everyone coming in is willing to wear masks.”

Originally named “Mac’s Town” after J.D. McMillan, a superintendent for the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Co. that established the town in 1923, it quickly morphed into Maxville and lasted until 1933. From Maxville, virgin Ponderosa pine timber was cut and hauled by rail to the Bowman-Hicks mill at Wallowa or to mills in La Grande.

To perform the work, the Missouri-based lumber company recruited experienced loggers from its home area. Trice’s father, Lafayette “Lucky” Trice and the latter’s father, were two of those who came from Arkansas in the early 1900s to help populate one of the largest African American communities in Northeast Oregon.

At its peak, Maxville had about 400 residents, 40 to 60 of them African American. Many of the rest were of Greek extraction. It was the largest town in Wallowa County during its lifespan, according to Trice’s entry in The Oregon Encyclopedia.

Trending

During its heyday, Bowman-Hicks jobs were typically segregated based on ethnic origin. Black workers felled the trees in teams, using cross-cut saws. Many had experience as log loaders, log cutters, railroad builders, tong hookers and section foremen, but in Maxville, the primary use of their expertise was log cutting, and there are firsthand accounts of Black workers repairing and maintaining the railroad engine. The Greek workers at Maxville had expertise in railroad building and white workers worked as section foremen, tree toppers, saw filers, contract truck drivers and bridge builders.

The town had a post office, medical dispensary, company store, hotel, horse barn, a blacksmith and roundhouse to turn the log-train engines. The buildings, manufactured at the local mill, were brought to Maxville by train on skids.

Only one structure remains from that boom time — a large log building where Bowman-Hicks ran the business. The building also served as a meeting place for residents of Maxville.

The town also had schools — one for white and one for Black students — and two baseball teams, again segregated. This segregation would disappear when they competed against teams from other towns by putting their best players all on the same team. A sample of one of the Maxville baseball uniforms is at the center in Joseph.

This was a time when the Oregon Constitution included a provision excluding Blacks from the state.

“When the state was admitted to the Union (in 1859), it was supposed to be a ‘white utopia,’ and Blacks just weren’t allowed,” Trice said. “It was the only state in the Union that joined with those exclusion laws in place.”

She noted that despite federal laws prohibiting such discrimination, Oregon’s exclusion laws remained on the books until 1926.

She told of one man, Jacob Vanderpool, “convicted of the crime of being Black” and expelled from Oregon. According to www.mic.com, in 1851, Jacob Vanderpool — the owner of a saloon, restaurant and boarding house in Salem — was a Black resident who was kicked out of the territory because of the law, even though, according to Salem Public Library records, the law was intended to prevent new Black people from settling in the region, the Washington Post reported in 2019. A judge expelled Vanderpool from the territory, giving him 30 days to leave.

“That’s unacceptable,” Trice said. “There was a different mindset then and it still exists.”

But she doesn’t get into the politics of it all. While she acknowledges that there are portions of the nation’s history that have a dark side, such as slavery and Jim Crow, that’s not Trice’s purpose with the Maxville center.

“I really don’t comment on it,” she said. “We’re doing our own Black lives matter here because it’s not just about Black lives, but Black lives do matter. Period.”

Oregon’s exclusion laws didn’t stop Maxville from thriving and contributing to the Oregon and Wallowa County economy and culture.

Maxville lasted until the depths of the Great Depression, when bank closures and an accompanying downturn in the timber industry forced layoffs and mill closures and Bowman-Hicks closed the town in 1933. The town died quickly and many of the loggers moved to other areas of Oregon to continue their trade or to find new ones.

Trice’s father joined one of the former Greek loggers in establishing a business in La Grande. Many went to work in the Portland shipyards where they contributed greatly to the shipbuilding efforts a decade later during World War II.

But after the war, Trice said, Portland city fathers contacted the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and said, “We’re done with these people. You can take them back to where they came from.” But the NAACP said, “We don’t do that. These are your residents of your state.”

Many of these things Trice has learned in her efforts operating the Maxville center. Born in La Grande and spending 20 years in Seattle working for Boeing, she believes her mission is to document what went on in Wallowa County.

“It’s about people — not just Black people. It’s about respect,” she said. “My family taught me to love my community and to support my community and if my dad hadn’t been in Wallowa County, in Union County, in Umatilla County and in Baker County doing all of those things in those communities and supporting the youth and the elders, the conservation, the land, the wildlife, I couldn’t do the work here.”

JOSEPH — Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center is planning a fundraising gala Saturday, Oct. 24, in an effort to raise money to fund efforts to promote the history of the onetime Wallowa County logging town.

The gala will take place from 5:30 p.m. to 8 p.m.

Also, the center is hoping to hire a docent and several volunteers. They would be responsible to greet visitors to the center and to acquire enough knowledge of exhibits to explain them.

The center is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Friday through Sunday. Visitors can call for a private tour other times during the week.

For more information, call Gwen Trice, the center’s founder and executive director, at 541-426-3545; email gwen@maxvilleheritage.org, visit the center’s website at maxvilleheritage.org or the center’s Facebook page.

— Chieftain staff