Wolf call: Oregon ranchers frustrated by criteria of state investigators

Published 2:00 pm Thursday, June 18, 2020

- Joseph Creek runs through a steep canyon in northeast Oregon, where Rod Childers and RL Cattle Co. graze cows during the summer.

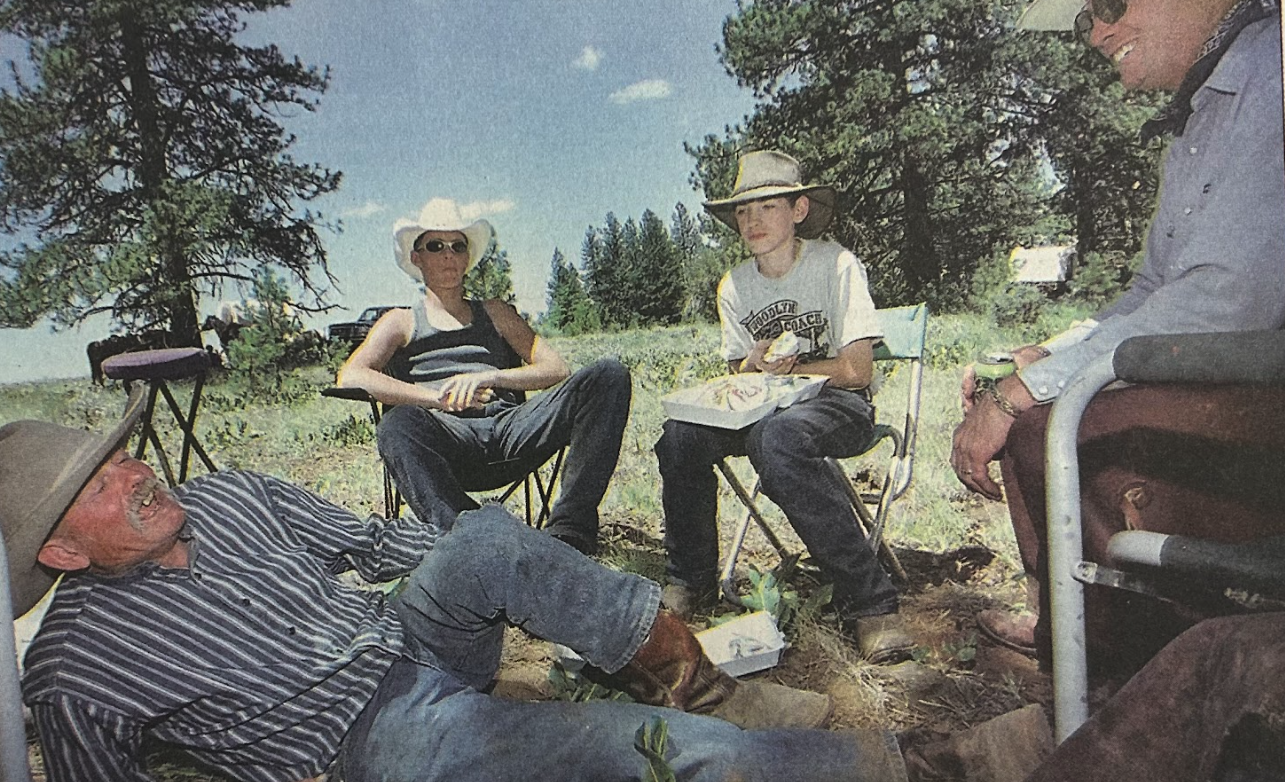

ENTERPRISE — Two days after Easter, rancher Rod Childers rode on horseback down Joseph Creek Canyon in far Northeast Oregon, herding cattle through the steep and remote countryside.

His dogs were the first to spot the dead calf, its carcass chewed down to the bones. Instinctively, Childers suspected wolves. But rather than report the gruesome discovery to state wildlife biologists, he simply cursed to himself and kept going.

The reason, he would say later, was the rigid criteria state biologists use to confirm whether wolves had indeed killed the calf. That, plus the fact that evidence of wolf-related trauma was already lost to scavengers or the elements, made the effort futile despite the fact the Chesnimnus pack had been seen in the area.

“You can go murder somebody and be convicted quicker than you would convict a wolf, with the criteria they have,” said Childers, owner of RL Cattle Co. in rural Wallowa County, where livestock and poultry sales totaled more than $23 million in 2017. “It just makes it so difficult that ranchers have given up on it.”

The issue boiled over again April 16, when the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife released its annual wolf report documenting 158 wolves statewide in 2019 — a 15% increase from the previous year.

Yet, the report also showed the number of confirmed attacks on livestock decreased 43%, which agency officials described as an indication that modern management techniques and nonlethal deterrents are helping wolves and ranchers peacefully coexist.

Some Eastern Oregon cattlemen, however, say it is less about coexistence and more about being hamstrung by ODFW and its requirements for investigating depredations. By the time a state biologist arrives at the scene, what little remains of a dead cow or calf cannot be definitively linked to wolves.

Whether wolf depredation is confirmed may impact how much, if any, money ranchers receive in compensation from the state. In some cases, ranchers say it isn’t even worth calling the state to investigate, certain they will not be fully compensated.

“I’m pretty bitter over it,” Childers said. “I’m 20 years into this stuff. It’s not fun. It’s not right.”

Investigations

ODFW investigated 50 suspected cases of wolves attacking livestock in 2019. Of those, 16 were confirmed. One incident was ruled a “probable” wolf depredation, 12 were “possible or unknown,” and 21 were determined to be not wolf-related.

That is a sharp reduction from the 71 investigations and 28 confirmed attacks in 2018, when the state’s minimum wolf population was 137.

While the state’s known wolf population has increased steadily over the last five years, the number of depredations on livestock has yo-yoed over the same period. In 2015, the agency confirmed nine attacks. In 2016, the total jumped to 24, and in 2017 it fell again to 17.

Derek Broman, state carnivore biologist for ODFW, said investigations are heavily evidence-based. Biologists look for telltale signs of wolves, such as tracks and physical trauma to livestock.

A wolf’s bite mark is unmistakable compared to that of other predators such as coyotes and cougars, Broman said.

“If you’re trying to look for wolf signs with a microscope, then it’s not a wolf,” he said. “You’re just going to see, it’s like a bomb went off.”

Reports must be confirmed by ODFW for ranchers to receive direct compensation from the state through a fund administered by the Oregon Department of Agriculture. The program also pays for missing livestock and for nonlethal tools, such as hiring range-riders or installing flashing lights and alarm boxes to keep wolves away from cattle.

Broman said he believes there were two reasons for fewer calls and confirmed depredations last year.

First, ranchers are becoming more experienced at recognizing the evidence of a wolf attack, he said. If it doesn’t fit the bill, they don’t report it.

Second, ranchers are using more nonlethal tools to prevent conflicts.

“A lot of these folks are doing things to keep depredations down, which helps the bottom line,” Broman said.

It also helps protect wolves directly. Under Phase III of the recently updated Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan, ranchers can apply to ODFW to kill wolves that prey on livestock two times within nine months — defined as “chronic depredation.”

Losing faith

Eastern Oregon entered Phase III of the wolf plan in 2017. That means the region had at least seven breeding pairs of wolves for three consecutive years.

Gray wolves were removed from the state endangered species list in 2015, though they are still protected under the federal Endangered Species Act in the western two-thirds of the state, west of highways 395, 78 and 95.

Childers was on the wolf committee of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association when the plan was originally adopted in 2005. He said Phase III was supposed to be the benchmark when wolves would be treated more like other predators around the state, with management zones and population caps up for consideration.

Instead, Childers said, ranchers were largely ignored during the latest plan revision adopted by the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission last summer.

“We didn’t get anything we didn’t already have in that plan,” he said.

RL Cattle runs about 400 mother cows and calves on both public and private land. In June 2018, wolves injured three of Childers’ calves in three days, and ODFW granted him a 10-day permit to shoot one wolf in the same pasture. Two months later, after wolves killed another calf, ODFW reissued the permit for 30 days.

However, Childers was never able to fire a single shot. He criticized the permit for being overly restrictive.

“It’s very rare you get a chance to see these things,” Childers said. “(ODFW) wouldn’t come out and help me. I had to do it myself, which is damn near impossible.”

In the case of his dead calf in Joseph Canyon, Childers said it was already too degraded and consumed for ODFW to confirm it was killed by wolves.

“There’s not enough left for them, by their criteria, to say yes, a wolf killed this,” he said. “The criteria is what needs to change.”

Local control

Rodger Huffman, who ranches 23 miles southeast of La Grande, had a similar experience.

In April 2016, Huffman turned out his cattle to graze on a 167-acre pasture along Catherine Creek, where the forest meets the meadows. Five days later, he returned to check on the herd, finding one calf eaten all the way through its rib cage. Trampled grass around the carcass indicated a struggle took place.

By that time, though, it was too late. Without enough evidence remaining at the scene, ODFW ruled it a “possible/unknown” wolf attack.

Huffman is no stranger to predators. He worked as a government trapper for USDA Wildlife Services for five years, and spent 31 years with the Oregon Department of Agriculture running the agency’s livestock inspection and animal health programs.

Though he cannot say with 100% certainty that wolves killed his calf, Huffman said it was unusual enough to raise suspicions.

“This is not a normal range scene,” Huffman said. “This calf did not just lay down and die.”

Huffman is now co-chairman of the Cattlemen’s Association wolf committee. One proposal frequently suggested by the group is to allow local sheriffs and veterinarians to investigate depredations, since they can often respond more quickly than ODFW biologists.

Fred Steen, chief deputy of the Wallowa County Sheriff’s Office, said he’s participated in more than 100 wolf-livestock investigations in his career. Ranchers, he said, want some assurance that wolves will be dealt with swiftly if they prey on livestock.

“I know these producers are frustrated,” he said. “It’s like an act of Congress to get a confirmation.”