Interpath solves supply chain issues and Heppner hospital receives rapid testing kits

Published 5:00 am Saturday, April 18, 2020

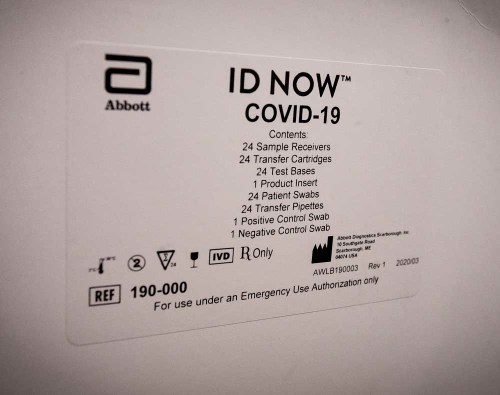

- A list of included supplies is printed on the outside of a box of COVID-19 quick testing equipment sent to Pioneer Memorial Hospital in Heppner.

PENDLETON — Politicians and health experts puzzling about how and when to restart the economy acknowledge a huge blind spot in data.

They really don’t know how many people coronavirus has touched because only the sickest of the sick are being tested. That has to change, they say.

What’s becoming clear is that the disease often goes into stealth mode and many with COVID-19 remain symptom-free. Consider the ongoing testing of 4,800 sailors on the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt. About 60% of 600 testing positive so far were asymptomatic.

According to the Umatilla County Public Health Department, 24 residents have tested positive out of the 481 tests conducted in the county since March 2.

While data collected by the Associated Press estimates roughly 3.4 million people have been tested in the U.S. at a rate of about 10.46 tests per 1,000 people, Umatilla County residents have been tested at a rate of about 6.16 per 1,000 people.

According to state data, Morrow County has five confirmed cases out of 58 total tests run, which is good for a testing rate less than half the national average at 5.0 per 1,000 people.

Umatilla County then kicked out a “trend map” on Tuesday, which shows the most cases in the county are located in the Hermiston-Umatilla area. But Umatilla County Public Health Director Joe Fiumara said it’s hard to say how accurately it represents the nature of the local outbreak.

“This doesn’t mean there’s more of the virus in the Hermiston-Umatilla area,” he said. “Testing hasn’t been equitable across the county for a variety of reasons.”

Only by increasing testing will we know the full picture of COVID-19.

Locally, efforts to ramp up capacity are emerging on a couple of different fronts despite some daunting barriers.

Testing coming soon to Pendleton lab

Interpath Laboratory, headquartered in Pendleton, will soon start in-house testing for COVID-19.

The nation’s quest to solve testing capacity limitations has been a rough road filled with potholes. No one knows that better than Judy Kennedy, Interpath’s marketing director.

She said that Interpath, which serves five states, sought to do its own in-house testing early on, but faced frustrating supply chain issues. The lab already had the necessary equipment to run the tests, but struggled to find a reliable and consistent source of reagents, the chemical that mixes with the person’s nasal swab to yield a positive or negative result. Those supplies seemed to flow to the bigger national labs instead of smaller, regional facilities like Interpath. Kennedy said reagents were being directed toward high-impact areas.

“We were beating every door down to find reagents,” she said.

So Interpath sent tests to ARUP Laboratory, a national lab located in Utah. When ARUP eventually got overwhelmed, Interpath’s tests were forwarded on to LabCorp, which also maxed capacity and forwarded tests to Quest. This flow from lab to lab brought frustration, took precious time and tested the ingenuity of laboratories, Kennedy said. At one point, many specimens collected from around the Pacific Northwest sat in Interpath’s frozen storage ready to send, while labs dealt with capacity issues.

“We had a situation where specimens were piling up,” she said. “It was taking some labs two weeks to turn out results. We struggled terribly with this, trying to do the right thing.”

Turnaround time is better now — about 48 hours — and test kits are increasingly available. Interpath will soon be able to do its own testing and produce results within 72 hours.

“The venders we’ve been working with have told us they’re going to have reagents available very soon,” Kennedy said. “Contracts have been signed. By May 1, we’ll be able to test in-house.”

This diagnostic test analyzes swabbed tissue, using reagents to break open viruses to expose their viral genome and determining whether patients are currently infected.

“It’s unfortunate it’s taken this long,” she said. “We are incredibly thankful for the dedicated clinicians in our communities who were patient with this process and demonstrated their ability to provide excellent health care despite the scarcity of diagnostic testing.”

She praised Oregon lawmakers — Sen. Ron Wyden and Rep. Greg Walden — and the Oregon Public Health Lab as allies in the push to obtain testing reagents.

“Interpath is basically ready to go with the test equipment and is really blocked by the supply chain issue, getting the reagents and supplies to perform the test,” said Wyden last week by phone. “Rural Oregon is 3,000 miles away from Washington, D.C., and D.C. might as well be Mars. My job is to shorten the distance and help rural Eastern Oregon cut through the red tape. I just don’t want rural Oregon to become a sacrifice zone when you’re looking at issues like testing.”

Kennedy said progress toward doing in-house testing has been deliberate and painstaking. Some of the national labs touted an ability to do more tests than they could pull off in the time required to be diagnostically helpful, she said.

“The last thing we want to do is create something that is misinterpreted,” she said. “We want to give our providers accurate expectations.”

One reason labs got caught flat-footed is because they must run so close to the margin. Kennedy said Medicare’s reimbursement reductions in the last three years mean labs must watch costs and aren’t able to keep large stockpiles of supplies to meet a crisis like coronavirus.

“Labs don’t keep a lot of supplies on hand,” she said. “You are as lean as you can be. When coronavirus came, all the labs were in the same boat.”

She explained that the pandemic is something of a Catch-22. Because elective surgeries and procedures are not happening because of the pandemic, labs have experienced a marked drop in business.

“When the stay-at-home orders came, we saw a 40% decrease of the routine testing we normally do,” Kennedy said. “When you take away all that work, labs are faced with having to cut forces and still implement and perform COVID testing. It’s the perfect storm. It’s not been without a lot of consternation.”

Heppner begins rapid testing

Access to COVID-19 testing in Eastern Oregon may have gotten a lift last week when the state announced Pioneer Memorial Hospital in Heppner was one of three in the state to receive the first allocations of the Abbott ID NOW rapid testing instruments that were provided by the federal government.

The tests, which were also distributed to rural hospitals in Curry and Lake counties, can reportedly return positive results within five minutes and negative results within 13 minutes.

“No. 1, I think it’s going to be a big help to Eastern Oregon,” said Bob Houser, chief executive officer of Pioneer Memorial Hospital. “I think it’s going to be a great tool, especially when we have been sending tests off and sometimes it takes two to three weeks to get a result.”

Hospitals like Pioneer Memorial, along with primary care doctors and labs throughout the region, have had their testing efforts obstructed by a litany of obstacles. Fiumara said the Umatilla County Public Health Department had to offer help in at least one instance last month just to get a sample taken at the Heppner hospital transported to the state lab.

The hope is these rapid tests will be “a whole new ballgame” in the country’s testing capacity, as President Donald Trump has touted they will be, but there’s still a way to go before their effectiveness is truly known.

“Rapid tests sound great, and they’ll do a lot of good — if they work,” Fiumara said. “But rapid tests typically aren’t the most accurate tests we have.”

In an attempt to guarantee accuracy, Houser said the hospital’s first rapid test results must be sent to the state lab for validation when they come back negative. After a certain number of negative tests are confirmed — Houser didn’t know exactly how many were required — validating each result won’t be necessary. Positive results don’t need to be confirmed, he said.

Aside from accuracy, there’s also still not enough rapid tests currently available to truly make a dent in the area’s testing shortcomings.

Each state received 15 Abbott ID NOW instruments from the federal government to run the rapid tests, but only 120 test kits were included with the instruments. Due to the limited supply, the state focused its first rapid tests on rural areas and Pioneer Memorial Hospital received 50 test kits last week.

“I want to be very clear: the number of testing kits we have received from the federal government for these new machines does not even come close to approaching the need we have in Oregon right now,” Gov. Kate Brown said in a statement. “I am committed to working with our federal partners to secure additional test kits as Abbott and other companies ramp up their production capacity.”

Houser said the state has directed hospitals to reserve the limited number of rapid tests for frontline health care workers and other essential workers, such as law enforcement and first responders. There could be a rare exception made in the case of a doctor requesting a test for a patient with underlying health conditions, he said.

“It’s really not open to everybody walking in and wanting to get tested,” Houser said.

As access to the rapid tests is extended to other clinics and hospitals in the region, Houser said Pioneer Memorial may also be able to serve as a resource by using the instruments provided by the government to run them.

But as it stands, rapid tests are just another tool to be used in the response to COVID-19.

“They may end up being more of an avenue rather than something to hang your hat on,” Fiumara said.

Officials skeptical of antibody tests

As communities plan for reopening their economies, some, including Trump, have recommended the use of antibody tests that are hypothesized to reveal whether someone is immune to COVID-19.

However, the World Health Organization issued a statement Friday saying there’s no evidence such tests can show whether someone is immune and no longer able to become reinfected, and local officials are equally skeptical.

While these tests can reveal whether antibodies are present in someone’s blood, Fiumara said it’s unclear what that information tells us.

“We don’t know if that means that you’re immune to the virus, we don’t know if that means if you’re going to be an asymptomatic carrier, we don’t know if that means you’ve had it and recovered,” Fiumara said. “There’s just a lot we don’t know.”

Fiumara said the county health department is working with Interpath to develop their tests, and that he’d welcome the additional information that testing for antibodies and testing on asymptomatic individuals would provide.

Hopefully, that information will help confirm that those who become infected and recover are immune from the virus, otherwise COVID-19 may become a seasonal health concern to be addressed year after year.

“If there’s long-term immunity from this, that’s the best case for everyone,” Fiumara said.