Down the rabbit hole

Published 10:24 am Friday, July 17, 2015

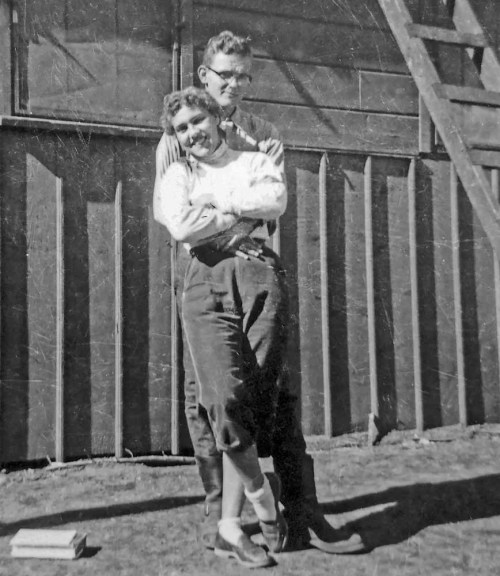

- Warren and Joyce Aney pose together at age 14 after meeting each other at a church camp in the Elkhorn Mountains. The couple married young and raised three children. Six years ago, they learned Joyce had Alzheimer's disease.

Hello Alzheimer’s.

About six years ago, my mother-in-law’s neurologist gave her news that no one wants to hear — she had Alzheimer’s disease. The heartbreaking diagnosis was a gut punch. We tried to imagine this outgoing, savvy woman just sliding away into oblivion — this mother of three, gourmet cook, singer, outdoorswoman, retired travel agent and center of family life.

Joyce Johnson and Warren Aney met at age 14 at a church summer camp. The Stanfield girl and the Umatilla boy immediately connected.

“She was the second girl I kissed,” said Warren, flashing back on his teenage self. “The first girl was a couple days before.”

Their personalities meshed in interesting and lovely ways, he said, and they married at age 19. The couple raised a family in Portland that included several foster children. They took the kids on cross-country ski trips and camping adventures in their Volkswagen minivan. They were a team.

After 55 years, the relationship shifted. Warren, a retired regional manager for Oregon Fish & Wildlife, spends his days taking care of Joyce. She is wheelchair-bound, so he shuttles her between different spots in the house — the bed, the toilet, the dining room table and the easy chair in the family room. He feeds her and makes sure she gets her medications. He takes her to church and parks her in the front row because “I want her in the center of things.” He is constantly tired, but committed.

“The alternative is not to have her here and that’s worse — not to be with her,” Warren said.

So he concentrates on each day, one at a time. He knows the ultimate trajectory down this rabbit hole, however, and says when the time is right for Joyce to move to a nursing facility, he will let her go. He refuses to dwell on that future.

“If you dwell on it, it could be depressing, but I don’t have time to dwell on it,” Warren said. “My obligation — my opportunity — is to take care of her as long as I can.”

Warren and Joyce aren’t alone in their daily struggle. As America ages, the number of people with Alzheimer’s rises. According to Stephanie Barnhart-Herro, program director of Oregon Care Partners, there are 60,000 Oregonians with the disease.

“The population is aging really rapidly,” she said. “By 2020, the number of Oregonians over the age of 65 will increase by 63 percent. The biggest known risk factor for Alzheimer’s is age.”

She said a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s can feel like having your world pulled out from under you.

“They’ve been given this really scary diagnosis, but are not really told what to do,” Barnhart-Herro said. “For caregivers, the stress is huge. That’s the other side of this disease.”

Caring for someone with Alzheimer’s is a daily slog. There’s no manual, though Oregon Care Partners offers online classes and trainings in various cities around the state.

“It’s a 24-hour-a-day job and oftentimes caregivers don’t have time to care for themselves,” she said. “According to the Alzheimer’s Association, it can last from two to 20 years. The way it progresses is different for everyone.”

Elaine Eshbaugh writes about the disease in her blog, “Dementialand.” The associate professor at Northern Iowa University is the Division Chair of Family Services and Gerontology and the daughter of my friend, Sue Dwyer. When Sue worked as activities director at a nursing home many years ago, young Elaine wandered among the residents.

“Some people are military brats,” said Eshbaugh, speaking Thursday by phone. “I was a nursing home brat.”

The little girl especially connected with residents who had dementia.

“They were in a different time and place,” Eshbaugh said. “They were the best playmates ever.”

Her unique blend of experience, education, research and counseling means Eshbaugh has plenty of road-tested advice for caregivers. To stay sane, she advises family caregivers to:

• Take care of yourself. “We have a culture of independence and a superhero mentality. Your health has to be as important as their health. This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

• Pick your battles. She tells the story of a woman with Alzheimer’s who spent three hours a day loading the dishwasher with clean dishes, then unloading and repeating. “It drove her family crazy, but it made her feel useful. In the end, they came to terms with it.” Another person read the same chapter of a book over and over. Eshbaugh sees no problem with this behavior. “Sometimes we create problems when there aren’t any problems.”

• Learn that being totally honest is sometimes not the right thing. She told of a woman who repeatedly asked when her long-deceased mom would be coming home. Instead of setting her right, her caregiver learned to say, “She will be back soon.” “We call this ‘therapeutic fibbing’ or stepping into their reality.”

Eshbaugh also urges caregivers to do as Warren does and focus on the day. In addition, she advises caregivers to forget about people who aren’t supportive, to accept help, forget feeling guilty and have a sense of humor.

“Figure out what makes you laugh and actively seek that out,” she said. “And don’t feel guilty for laughing.”

Warren echoed Eshbaugh’s advice to take care of yourself first. After injuring his back during a lift, he learned lift techniques and vowed not to take chances with his own health.

Joyce’s short-term memory has faded, though she still has some long-term recollections. She stays quiet most of the time, but sometimes pipes up unexpectedly.

The other day, Warren toiled over a crossword puzzle. When he couldn’t remember the name of “Lucy’s husband,” he asked Joyce.

“Desi,” she said.

Warren has learned to celebrate those moments of connection. He smiled.

In a poem Joyce penned shortly after her diagnosis, she wrote “They say that eventually I won’t recognize my sweetheart of 50-plus years. What a heartbreak … Remember me as a compassionate, creative, giving soul who loves her life as it is, but not as it will become. Maybe this is just a bad dream. Please I’m ready to wake up now.”

Warren once asked himself whether he would have married his high school sweetheart had he known she would get Alzheimer’s and require years of caregiving. The answer, he said, came without hesitation.

“Our life together has been greatly enriched with wonderful children and grandchildren, with shared adventures and experiences, with jointly developed social and religious linkups, with similar but complementary appreciation and celebration of arts and nature,” he said. “Given this rich and rewarding relationship over so many years and the realization that Joyce is still partly able to maintain and appreciate this relationship, I would not have done it differently.”

———

Kathy Aney writes about human interest, health and other topics for the East Oregonian.