Teaching tools of the trade

Published 10:04 pm Monday, September 8, 2008

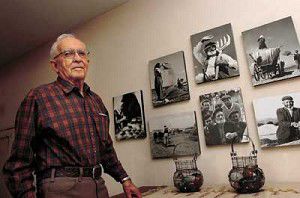

- Vance Pumphrey of Pendleton spent two years in Turkey with an Oregon State University wheat team helping government increase their wheat production.<br><I>Staff photo by E.J. Harris

In 1974, Pendleton resident Vance Pumphrey had an opportunity to travel with an Oregon State University wheat team to Turkey, where for two years they helped the government improve the country’s wheat production.

The work was through a contract with the U.S. Agency for International Development. Pumphrey traveled to different areas of the country but was based in the capital city of Ankara with his wife Niola.

Even on the other side of the globe, Pumphrey, a former agronomist, said the climate of central Turkey was similar to places in Eastern Oregon like Heppner, Condon or Moro. Comparable topography, rainfall and temperature made Oregon wheat production methods rather translatable.

And although the country was making great strides in production, there still were many hurdles to overcome.

The Turks did, for example, have an agriculture extension system, albeit a sometimes ineffective one.

“The extension agents were college graduates, but most of them lacked any field experience. Most of them had been raised in a city or large town,” Pumphrey said. “Because of their lack of experience, they had often sat in their office and seldom went to the villages.”

Pumphrey said the standard farming practices included both ancient and modern technology.

“The team estimated about one third of Turkish wheat was produced by methods used in Biblical times,” Pumphrey said.

That included hand sowing, reaping with a scythe and winnowing wheat in the wind.

Another third of production, he said, utilized modern methods like drilling, weed control and combine harvesting. And the rest fell somewhere in the middle.

Pumphrey said there was a factory in Turkey that made John Deere combines, but only one model. Having one model, however, greatly simplified things like small parts distribution and repairs – especially for a people not yet accustomed to machinery.

“Mechanization of wheat production increased food supply but also created immense social problems,” Pumphrey said, explaining many villagers lived on a subsistence basis – not a cash income.

Pumphrey said the villagers who produced wheat often would band together to purchase a tractor and machinery. Unfortunately, that left one man able to do what had been the job of many, eventually leaving hundreds of thousands in Turkey severely underemployed.

Overall, Pumphrey said the country had a lack of published research pertaining to wheat production. So for about a year, he worked to compile a production manual for the country, which was translated from English and eventually used in other Middle East countries as well.

The two years in Turkey weren’t only about wheat but a memorable cross-cultural experience, especially for Niola.

While he was conducting his ongoing work, she maintained the couple’s apartment in the embassy district.

Immediately upon arrival in Turkey, Pumphrey said they were asked to get a maid, an idea to which Niola – very capable in her domestic duties – was initially resistant.

“In about a month, a Turkish woman appeared at the apartment door and said in her very limited English that she was our maid,” Pumphrey said. “Niola accepted her and enjoyed her very much.”