Aquifers allow easy, underground movement of irrigation water

Published 10:34 am Wednesday, October 31, 2007

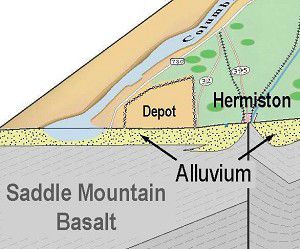

- A three-dimensional view of the landscape and its underlying aquifers in part of the lower Umatilla basin. Graphic of the Umatilla County Critical Groundwater Task Force

Irrigated farms that use groundwater depend on a complex natural system of pores and holes within and between rocks to supply water to their wells.

These underground piping systems are called aquifers. Aquifers allow the relatively easy movement of groundwater from one place to another, usually by gravity.

Trending

In the Umatilla River Basin, some aquifers are made up of gravels, sands, and clays that move water through the spaces within the seam. Ancient streams laid down these seams. They are called alluvial aquifers from the word “alluvium,” which geologists use to refer to the cobbles and gravels left by fast-moving streams during runoff periods.

The other type of aquifer in the basin occurs in deep basalts where the cracks within the rocks and between lava flows provide a passage for groundwater. You can see both types of aquifer in the drawing that accompanies this article.

Many of our alluvial aquifers are near the Columbia River. Generally, alluvial wells in the Umatilla Basin are between 50 and 250 feet deep. The deepest one I know about is 275 feet deep near Hinkle. Wells into alluvial aquifers are relatively cheap to drill and operate because they are not very deep and gravels are porous and transmit water readily.

Because they are recharged annually from the land surface, alluvial wells may be less productive during droughts than basalt wells.

Deep basalt wells in the Umatilla Basin range from about 250 feet to 2,050 feet deep. They have been drilled into basalt rock laid down by periodic eruptions of fluid lava between 6 million and 17 million years ago. These layers of basalt were tilted up when the Blue Mountains were raised, allowing water to move underground by gravity from the mountains to the Columbia River.

Movement underground provides water to the deep basalt wells in the lower Umatilla Basin. This underground movement is slow. The average age of water in the deep basalt wells of the lower basin is 16,500 years. The water in these deep wells has had to move through cracks within and between the layers of rock.

Trending

In places, this downhill flow is hindered by the layers being offset by faults where the layers are displaced. Since the Blue Mountains arose, movement of surface water and ice flows have carved out the landscape features of the Umatilla River Basin.

From the time of European settlement in the mid-1800s until the 1950s, most irrigation water for farming came from surface waters using gravity distribution and flood or furrow irrigation. In the 1950s we began to use significant amounts of groundwater applied with pressurized sprinkler systems. The great increase in groundwater use came after 1966 when center pivot technology allowed irrigation of land that was somewhat hilly and had minimal labor requirements for moving pipe.

Withdrawing water faster than it is being replaced has brought the lower Umatilla basin to the current critical groundwater crunch that caused the Umatilla County Critical Groundwater Task Force to be established.

Sam Nobles, a member of the Umatilla County Critical Groundwater Task Force, is a retired farmer and state brand inspector. In 1944, he began dealing with water use in the lower basin as a nine-year-old boy helping flood-irrigate his family’s 100-acre farm.